Egypt’s gas and Vision 2030 [NGW Magazine]

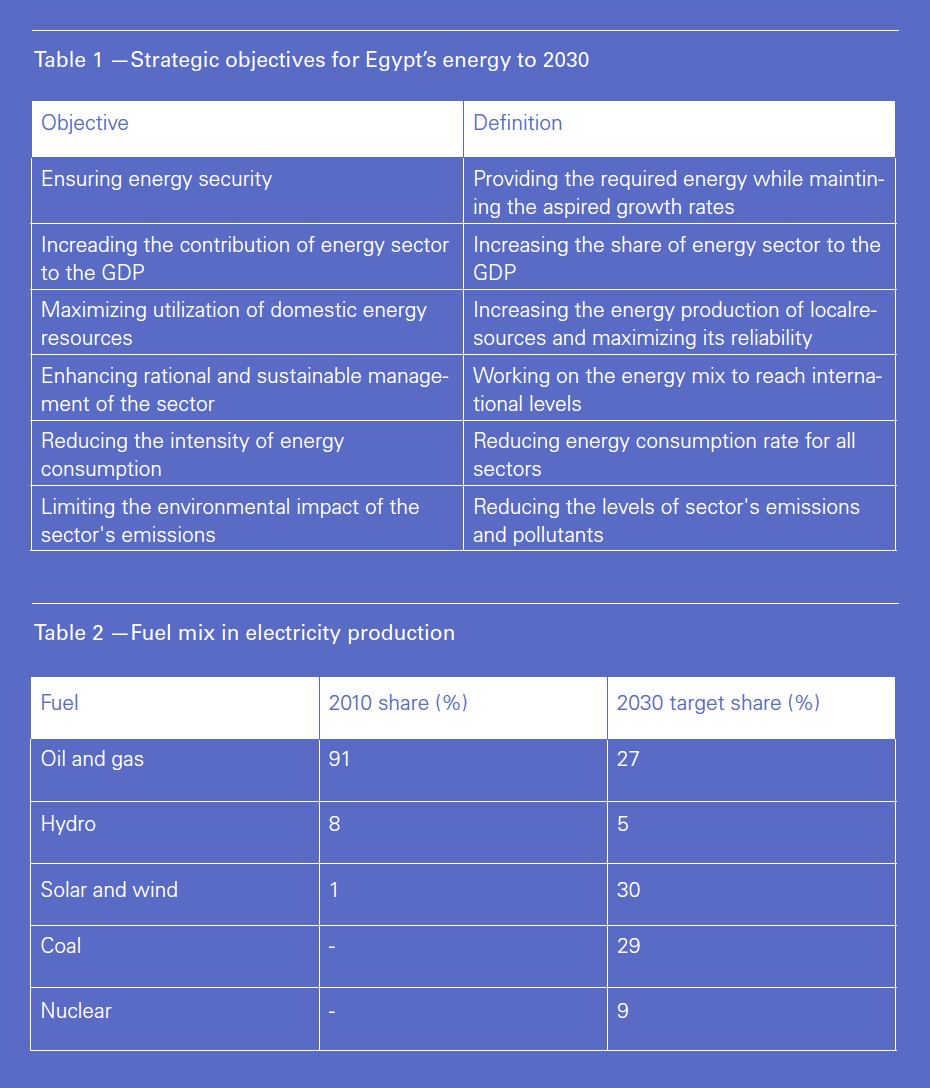

The key strategic objectives for Egypt’s energy to 2030 are summarized in Table 1.

The first priority is achieving energy security, by increasing production and providing the energy supplies required by the country’s domestic market, industry and households.

Vision 2030 includes key performance indicators to be achieved by 2030, taking 2010 as the base year, such as:

-

Reduction of the oil and gas share of electricity production from 91% in 2010 to 27% in 2030 (Table 2);

-

Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from the energy sector by 10%;

-

Elimination of fuel subsidies by 2020;

-

Reduction of energy intensity – defined as the ratio of total energy use to GDP – by 14%;

-

Increase in the contribution of energy to the country’s GDP to 25%.

Vision 2030 identifies key challenges to be overcome, such as:

-

Investors distrust the government to commit to financial responsibilities;

-

No specific agency is responsible for implementing a strategy for the sector and there is no energy regulator;

-

Competition between the private and public sectors is unfair;

-

Consumers are unaware of the importance of energy conservation.

Several programmes have been identified to address these challenges and implement Vision 2030. These include:

-

Restructuring the energy sector, its infrastructure and the legislative framework;

-

Promoting innovation and skills;

-

Applying environmental standards; and

-

Establishing a nuclear power station at Dab’aa.

All of these are already at an advanced stage of implementation, as described in earlier Natural Gas World feature articles in Volume 2, Issue 16 and Volume 3, Issue 9.

A success story

The recent pronouncements by Egypt’s petroleum minister Tareq El Molla have shown the confidence the country now has in its energy sector. It is witnessing record natural gas production allowing even for LNG exports; it is generating surplus electricity which can be exported; and this abundance has made possible the lowest ever fuel subsidies.

All major and a number of minor international oil companies (IOCs) are now operating in Egypt, and announcing a succession of gas discoveries (Figure 1).

This massive reversal of fortunes – from the pre-2014 stagnation in oil and gas exploration and production that led to the need to import LNG to today’s surplus gas production and LNG exports – is due to the successful implementation of reforms – and determined implementation of Vision 2030.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s $12bn loan to Egypt in 2016 not only helped shore up its economy, but it came with strings attached: the government had to reform the economy; liberalise the currency; introduce a gas-pricing mechanism that incentivised foreign investment upstream; and privatise the gas sector. That loan programme is now complete and the success is there to be seen.

In 2012, Egypt owed IOCs $6bn for production it had taken but not paid for. By the end of June these were reduced to $900mn and El Molla expects them to be settled by the end of the year.

Likewise, fuel subsidies totalled $22bn in 2010, or about 7.5% of Egypt’s gross domestic product – a major drain. But after their gradual removal over the last three years, by early 2019 fuel prices were brought close to 90% of their international cost. This led to a reduction in fuel subsidies to about $3.2bn in the financial year 2018-19. Egypt now expects to eliminate most fuel subsidies by 2020, as envisaged in Vision 2030. The resulting higher fuel and energy prices have led to a more efficient use of energy.

But this does not include natural gas used for power generation, which is still pegged at $3/mn Btu, well below production costs. This must eventually be addressed.

Impact on energy consumption

There are already clear signs that these reforms, especially the removal of fuel subsidies, are cutting energy demand growth. It is estimated that in 2019 electricity demand actually fell almost 4%, generating a surplus in supply.

According to BP’s Energy Statistical Review 2019, Egypt’s primary consumption in the ten-year period from 2007 to 2017 rise by an average 3.2%/year. The increase in 2018 was well below this, at 2.1%. And gas demand growth was 6.6% – just half the increase in 2017.

Egypt’s renewable energy outlook is also benefiting from implementation of Vision 2030, with technical assistance from the Danish Energy Agency and investment from the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development and international investors. In order to meet greater demand, the Egyptian government developed an energy diversification strategy, known as the Integrated Sustainable Energy Strategy (ISES) to 2035, to ensure supply remained secure and stable. This strategy involves stepping up the development of renewable energy and energy efficiency.

The International Renewable Energy Agency (Irena) carried out a review of ISES and Egypt’s renewable energy and its potential and published the results and its recommendations in a detailed report in October 2018.

Irena concluded that Egypt is committed to the widespread deployment of renewable energy technologies and has ample potential to achieve its ambitious Vision 2030 targets, “as it enjoys an abundance of renewable energy resources with high deployment potential, including hydropower, wind, solar and biomass.” Irena found that Egypt could realistically and cost-effectively supply as much as 53% of its electricity mix from renewables by 2030.

Egypt has embarked on an ambitious renewable energy implementation programme and it is on course to produce 20% of its electricity from renewables by 2022. Its annual renewable electricity production has now reached 6 GW, with about a third coming from wind and solar power.

This will be boosted further by the end of the year, when the Benban complex, the world’s largest solar installation, is completed. It is expected to operate at 1.6-2 GW.

As a result of the success in slowing down energy demand growth at a time when electricity production capacity has been increasing steadily, Egypt’s electricity ministry is now considering postponing planned electricity plants. It is even considering exporting over-production to neighbouring countries.

The full impact of the energy reforms on bringing Egypt’s increasing energy consumption under control is still to be realised, but these, combined with the increasing use of renewables, and increased gas production are freeing gas for export.

Impact on natural gas production and exports

Egypt’s gas production turnaround started with the discovery of the giant Zohr gas field in 2015, holding 30 trillion ft³ gas. It was brought on line at a record time – 30 months from discovery – and it is now producing 2.7bn ft³/d. That was the target for the end of the year, meaning it is about five months ahead of schedule. Zohr production is expected to reach 3.2bn ft³/d by 2020, with the addition of another nine production wells.

Zohr contributed to Egypt achieving natural gas self-sufficiency by October last year. According to the Central Bank of Egypt, this led to Egypt’s hydrocarbon trade balance registering an $800mn surplus during Q4 2018, its first since 2013. This is an amazing turnaround for a country that spent $3bn importing LNG in 2016.

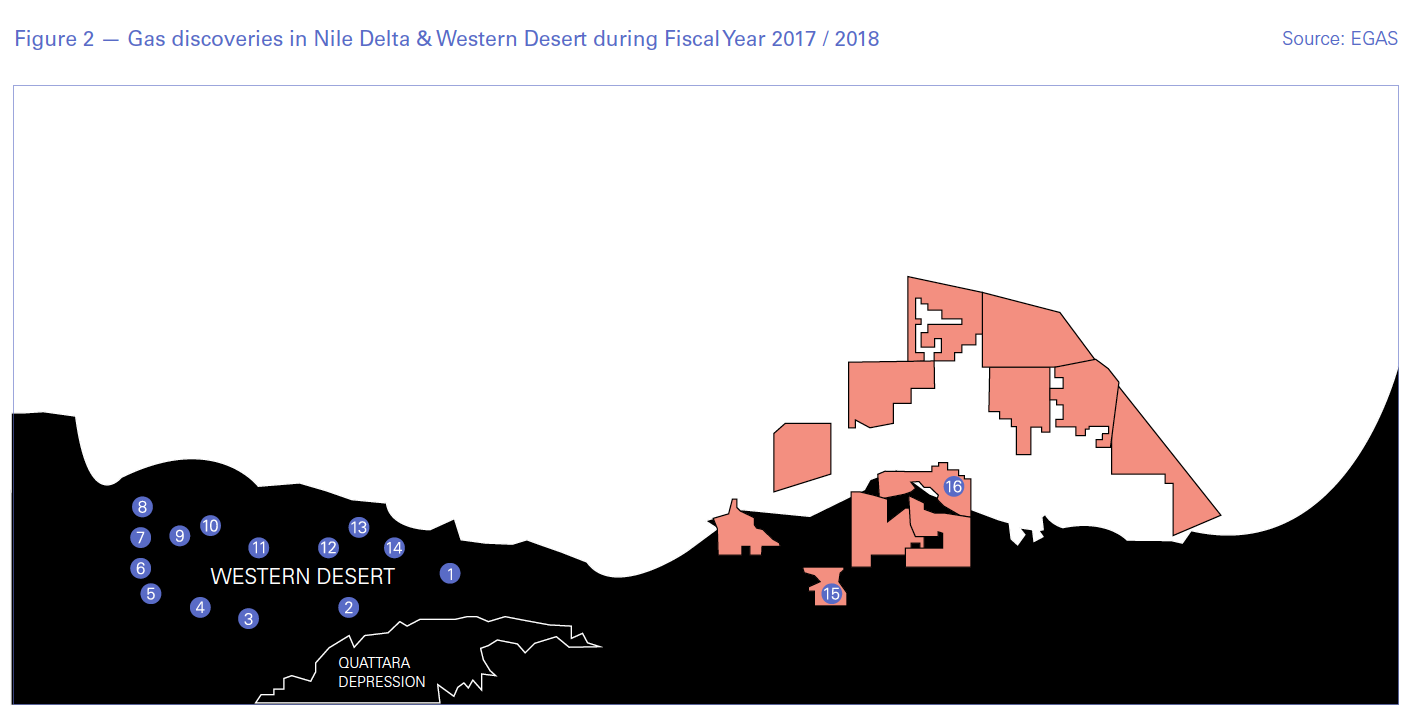

But it is not just Zohr. New discoveries are being made continuously. In March Eni announced the discovery of Nour, but has not yet given indication of its size. Smaller discoveries were also announced by Dana Gas and Petrobel.

These were followed in June by BP announcing that it is about to bring on line another 250mn ft³/d from its Giza and Fayoum gas fields. Further, BP said that with completion of the third development phase by the end of 2019, production from all three phases of its West Nile Delta project (Figure 2), including the Raven gas field, is expected to reach about 1.4bn ft³/d. The company also aims to increase gas production at its Batim South West field to 500 mn ft3/d when development is completed by mid-2020.

These and the growing productivity of existing fields are compensating for the natural decline in the productivity of older fields, feeding increasing domestic demand and exports. In June Egypt’s petroleum ministry agreed to allow Eni and BP to export gas from the Zohr and North Alexandria fields through Idku, after meeting the needs of the domestic market and achieving production surplus.

The ministry expects gas production to reach 7.95bn ft³/d during the financial year 2019 to 2020, while domestic demand is expected to reach about 6.39bn ft³/d. The surplus 1.56bn ft³/d is close to the combined nameplate capacity of the Idku and Damietta LNG plants – Idku is already exporting 750mn ft³/d – and the ministry estimates that exports will earn $2bn for the country.

The ministry also intends to maintain gas supplies to Jordan. In March it raised the level to 350mn ft³/d from 100mn ft³/d in January. It is even in discussions to export gas to Lebanon.

Eni confirmed in July that it is in talks over restarting Damietta and that it expects it to be back in operation before the end of the year. This was indirectly confirmed by El Molla who said that all export facilities will be working at full capacity by the end of the year.

Also in June, the Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (Egas) announced that it aims to raise output by 4.8bn ft³/d by June 2022 through the development of 19 gas projects, bringing Egypt’s total gas production to about 11.3bn ft³/d.

The ministry is also opening up new blocks for further exploration. The last licensing rounds, the results of which were announced during EGYPS 2019 in February this year, were very successful, as 12 new exploration blocks were awarded (Figure 3). Among the winners were a number of IOCs: the European majors Shell, BP, Eni and Total; US ExxonMobil; and Malaysian Petronas.

Egypt launched a new offshore licensing round in March, tendering 10 blocks in the Red Sea, where it hopes to replicate Saudi Arabia’s recent successful discoveries. El Molla confirmed that the two countries are in discussions as they look into collaborating and exchanging data. Egypt is also considering tendering 11 blocks in the country’s western Mediterranean waters by the first quarter of 2020, or earlier, hoping for new, Zohr-type, discoveries.

In order to make undeveloped areas more attractive to the majors, Egypt is finalising investor-friendly, production-sharing contracts (PSCs). El Molla said: “We are improving the cost-recovery process to make it faster, less bureaucratic and more efficient.” Whilst the new PSCs are expected to pass all E&P costs to the IOCs, they will give them a greater share of the output and freedom to sell it at their discretion.

Egypt is hoping that the new PSCs will contribute to the success of the new licensing rounds and attract increased foreign direct investment (FDI) into the country, in addition to the $10bn expected in 2019. The IMF identified the need for sustained FDI as an important factor in supporting Egypt’s continued economic recovery. Extending the licensing rounds to include the Red Sea and western Mediterranean should also help maintain Egypt’s impressive hydrocarbon discovery rate and boost gas production to feed the country’s growing domestic market and exports.

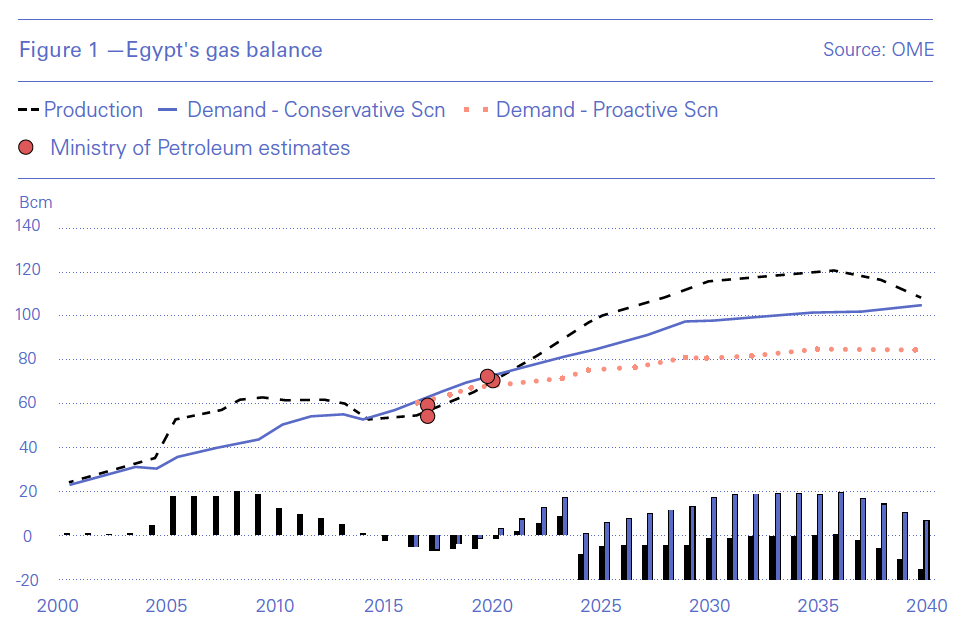

The hydrocarbons director at the Paris-based Mediterranean Observatory for Energy (OME) Sohbet Karbuz confirmed that OME expects Egypt's surplus gas available for exports to be between 17.5bn m³ and 29.5bn m³/yr by 2030 and between 7.5bn m³ and 25bn m³/yr by 2040 (Figure 4). These results, coming from OME’s supply-demand model for Egypt, are based on past data from its members and correspond to two demand scenarios, the reference and the proactive scenario. Actual demand could be between the two.

The Conservative Scenario (CS) is the reference scenario, taking into account past trends, current policies and ongoing projects and incorporates only unconditional Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

The Proactive Scenario (PS) is based on the implementation of energy efficiency programmes and increased diversification in the energy mix, assuming that Egypt’s NDCs will be met in full.

Of critical importance are the production forecasts. OME estimates production at 110bn m³ by 2030, peaking at close to 120bn m³ in 2037 and declining to 112bn m³ by 2040. So far, if anything, actual performance and the June production forecasts by the petroleum ministry indicate an even rosier future.

Egypt’s natural gas future looks to be going in the right direction.

Impact on Cyprus and Israel

Egypt’s aspiration to become the regional gas hub, led to the possibility of Cyprus and Israeli gas being exported to the country – depending on commercial terms – for its domestic market and for liquefaction and export from its two LNG plants at Idku and Damietta. Through such projects Egypt could end up holding the key to East Med’s gas export future.

The East Med Gas Forum (EMGF), which had its second meeting in July in Cairo in July (NGW #15), was formed to increase co-operation for the promotion and exploitation of natural gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean and pave the way for a sustainable regional gas market. The meeting discussed ways of co-operation on export corridors to make it easier to market known and future discoveries.

However, the statement issued at the end of the meeting did not indicate how or what steps the members would take to develop the region’s hydrocarbons.

But with the level of Egypt’s gas discoveries and the success of its energy reforms in bringing the growth in consumption under increasing control, mean that the country may no longer need imports, unless these are quite competitive in comparison to domestic gas prices.

With its LNG plants expected to reach capacity this year – according to El Molla – there may not even be room to handle Cypriot and Israeli gas.

The exception may be the deal between Noble Energy and Delek with Dolphinus Holdings. This is a commercial deal between private companies and may still go ahead. It has so far been experiencing problems and delays, but Delek is confident that it can start deliveries by November.

The possible deal to sell 0.7bn ft³/d Aphrodite gas to Idku – about 70% of Idku’s liquefaction nameplate capacity – for liquefaction and exports is risking becoming a victim of the increasing gas surplus in Egypt. An inter-governmental agreement to build a pipeline to bring this gas to Idku has already been signed and ratified by the two countries.

But for Aphrodite gas to secure a gas sales agreement with Idku, a number of steps are still needed, starting with another appraisal well. Then comes the front-end engineering and design, to get a better estimate of costs. Then comes price negotiations and the gas sales and purchase agreement if this is commercially viable. Then come talks with the banks and other financial entities. So that part of the process could take three years; and construction another three. So first gas deliveries are unlikely before 2025.

Challenges

Exporting Egyptian LNG is subject to global prices and current price levels pose a challenge to commerciality. Based on price, it is difficult to see Europe being the market for eastern Mediterranean gas and, with competition intensifying, Asia will not be easy if the Chinese slowdown continues.

The guaranteed minimum price paid by Egypt to offshore gas producers is $3.95/mn Btu, rising to $5.88/mn Btu depending on the field. Even though liquefaction costs from the two existing plants are low, once these and shipping costs are added it makes competitiveness in global markets challenging. It will become more so when Idku and Damietta reach full export capacity, meaning new capacity will be needed for imported gas.

The advantage of Egypt is that it has a growing domestic demand for energy to cater for its growing population – now nearing 100mn. But even then, if OME’s forecast is right (Figure 4), surplus gas is likely to exceed the combined capacity of its two LNG plants. Egypt should look into gas exports regionally to Jordan, Lebanon and possibly Saudi Arabia, so that it can make full use of surplus gas.

Restructuring and modernising Egypt’s energy sector has made a good start, but there is still a long way to go and momentum must be maintained. This includes seeing through the liberalisation of the gas market and a level playing field. The challenges identified in Vision 2030 have been partly addressed, but still need effort to see them concluded.

In its final review of the programme, the IMF praised the Egyptian government for executing a package of fiscal austerity measures which improved Egypt’s GDP and its economy and financial health, helped bring rampant inflation down from 33% in 2017 to 8.7% now and increased growth rate to 5.5% in 2018. However, the devaluation of the Egyptian pound and the removal of fuel subsidies meant that living conditions for a substantial part of the population have deteriorated: an estimated 32% of the population live in poverty, up 5% since 2015. These disparities need to be addressed.

Nevertheless, the determined implementation on Vision 2030 and the unquestionable turnaround of its hydrocarbons sector have set Egypt’s economy on a firm footing, with the potential to enjoy a sustainable and better future.