Divergence in US, European majors’ climate strategies narrows [Gas in Transition]

Growing divergence between US and EU oil and gas majors on climate goes back years. It peaked in 2020/2021. But since the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the ascendance of energy security ahead of climate change concerns, the gap has been narrowing.

During 2020, with the price of oil plunging, and even going negative in April, BP, Shell and Total at varying degrees reinvented themselves as clean energy providers, responding to EU’s goal for a fast transition to carbon-neutrality by 2050, believing that the world was moving into an era in which oil and gas would carry on a permanent decline trajectory. Stakeholder and shareholder pressure to commit to a transition in tune with EU’s goals was also much stronger than similar pressure in the US.

US majors, Chevron and ExxonMobil, adopted different strategies, unlike those of their European counterparts. While responding to pressure and recognising the need to reduce emissions, they stuck to their core business, prioritising lower costs and increased efficiency. Also, unlike Shell and BP, they steadfastly avoided making commitments to cut Scope 3 emissions, arising from consumer use of their products. Chevron CEO Mike Wirth said “we will find ways to make oil and gas more efficient, more environmentally benign.”

US majors believe that transition will be gradual and, with the world unwilling to embrace drastic changes to living standards, oil and gas will be needed for a long time to come. “The reality is, [fossil fuels] is what runs the world today… It’s going to run the world tomorrow and five years from now, 10 years from now, 20 years from now,” Wirth said.

This is also embodied in ExxonMobil’s SEC filing in May that stated "it is highly unlikely that society would accept the degradation in global standard of living required to permanently achieve a scenario like the IEA NZE [Net Zero Emissions by 2050]." ExxonMobil considers the likelihood of this scenario materialising remote.

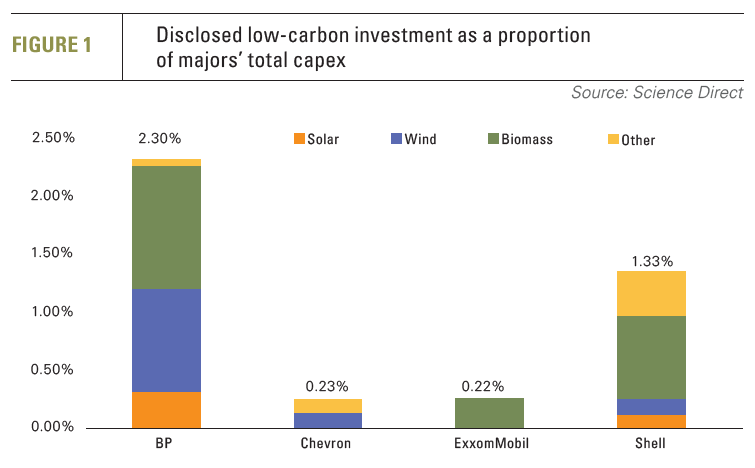

While European majors embraced climate change proactively and adopted strategies investing heavily in renewables and low-carbon projects (see figure 1), their US counterparts remained focused on the resilience of global oil and gas demand. An additional factor is that pressure from governments and activist groups is much stronger on European majors than on the American ones.

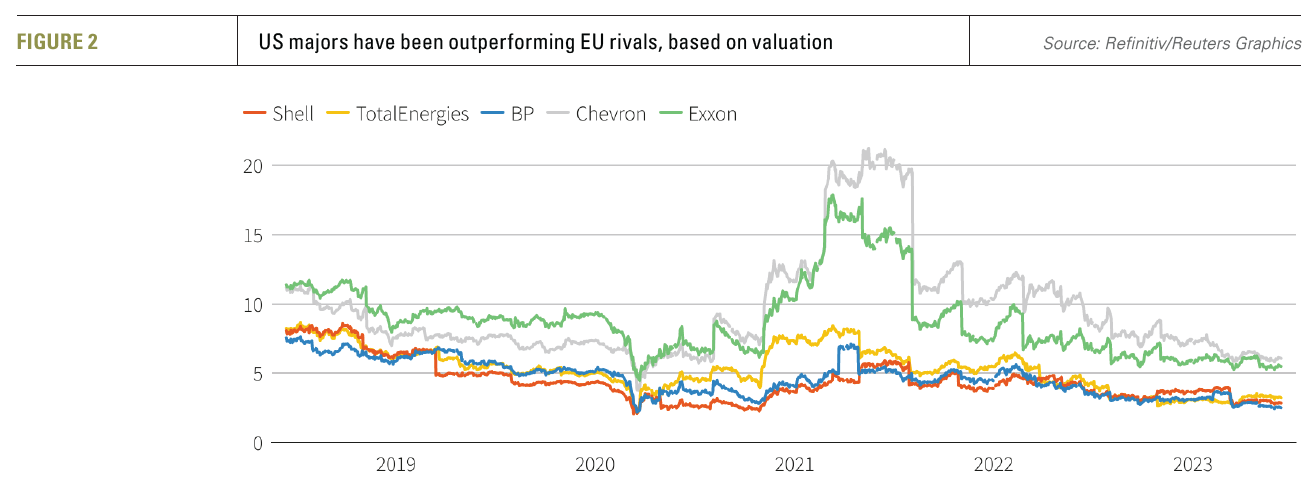

Evidently this strategy is paying-off. US oil and gas majors have been consistently outperforming their European counterparts (see figure 2). In order to get a better idea of how oil and gas companies are faring against their competition, a commonly used valuation measure is price-to-cash flow/ share.

Evidently this strategy is paying-off. US oil and gas majors have been consistently outperforming their European counterparts (see figure 2). In order to get a better idea of how oil and gas companies are faring against their competition, a commonly used valuation measure is price-to-cash flow/ share.

The valuation gap between US and European majors widened over the period 2019 to 2023. Just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the average valuation of US majors was about 70% higher than that of their European counterparts. The gap has now widened further, to well over 100%. This is giving rise to talk that European majors risk becoming takeover targets for US majors.

One interpretation of this gap is that shareholders are rewarding companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron that stay focused on their traditional, core businesses. For European majors, striving to respond to activist shareholders’ expectations of climate change policies in tune with the European Commission-led transition to low-carbon energy, does not appear to be a winning formula.

Shell’s new CEO Wael Sawan appears to have recognised this. According to the FT, he has promised “to focus on shareholder returns to close a yawning valuation gap against US rivals, which have remained more committed to oil and gas production and are valued at much higher multiples of their cash-flow.”

A recent survey has found that in the US, while a majority of Americans support becoming carbon neutral by 2050 and support US participation in international efforts to reduce the effects of climate change, they are reluctant to phase out fossil fuels altogether. They also see climate change as a lower priority than other national issues.

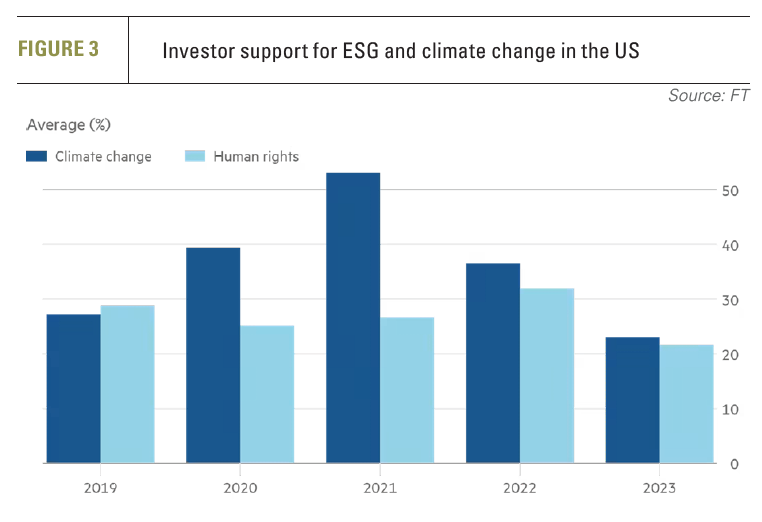

Investor pragmatism appears to prevail in the US and this is reflected in share prices. But, with energy security top of the list and bumper profits last year, even in Europe investor sentiment has now shifted.

About-turn in shareholder sentiment

The 2023 AGMs have shown a clear shift in shareholder sentiment towards ESG and climate activists. Now they are prioritising value. And that despite increasingly serious warnings from the UN and scientists to urgently reduce global emissions, resolutions demanding increased emission reductions are becoming fewer.

While transiting to clean energy remains important, energy security and rising fuel price concerns are taking priority over climate change concerns. And so are increasing indications that renewables are not ready to replace oil and gas in the global energy mix. Profitability is undoubtedly another major factor – returns from oil and gas vastly exceed the more modest returns from renewables.

Last year, ExxonMobil recorded a major victory after its shareholders supported its energy transition strategy at its AGM, with less than 20% backing a resolution urging faster action to fight climate change and with only 28% backing a proposal for setting and publishing medium and long-term targets to reduce Scope 3 emissions, as well as reducing hydrocarbon sales. In addition, in May this year a resolution calling for the company to set emission reduction targets that would be consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement got only 11% support.

In June, a similar resolution received less than 10% support from Chevron shareholders. Last year, they also voted against a resolution asking the company to adopt greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction targets, with only 33% supporting it. In effect, these endorse the steps already taken by the company to address climate change.

In this year’s AGMs, ExxonMobil and Chevron faced 13 resolutions related to climate change and carbon emissions, with just one receiving more than 20% support. Evidently, support for ESG and climate change is declining among US investors (see figure 3). With their shareholders behind them, both companies are committed to increasing their oil and gas output.

Despite backtracking on its earlier climate change commitments, an activist resolution to set tougher climate targets was rejected by BP’s shareholders in the company’s AGM in April. And a resolution to force the company to reduce oil and gas output faster received only 17% support.

At Shell’s AGM in May its CEO made clear that “renewable energy is not profitable enough to increase value for the shareholders.” A resolution calling on the company to speed up its energy transition plans received only 20% support.

These outcomes represent a massive change – and a reality check - compared to 2021, when activist shareholder resolutions forcing the majors to adopt various measures to address climate change received widespread support.

Change of direction by European majors

In February, European majors saw their share prices climb as they reported on their bumper 2022 results and announced plans that involve a return back to their traditional, core, business. Evidently, investors buy into a company not because of its climate change plans but because of its profitability and shareholder returns plans.

In February BP scaled back climate targets and now plans to produce more oil and gas for longer. The company said it would continue to work towards reducing emissions by cutting oil and gas production, but it revised its target for these production cuts.

It will now reduce Scope 3 emissions from its own oil and gas production to 20-30% from 2019 levels by 2030, in comparison to 35-40% set previously. BP also announced earlier that it will increase investments in oil and gas by around $1bn/year. Justifying this, BP CEO Bernard Looney, said “governments and societies around the world are asking companies like ours to invest in today’s energy system.”

Shell is also changing direction. It confirmed on June 14 that, while remaining committed to reducing emissions to net zero by 2050, it now plans to keep its oil production steady to 2030 and spend more on expanding its successful and profitable LNG operations by as much as 30% by 2030.

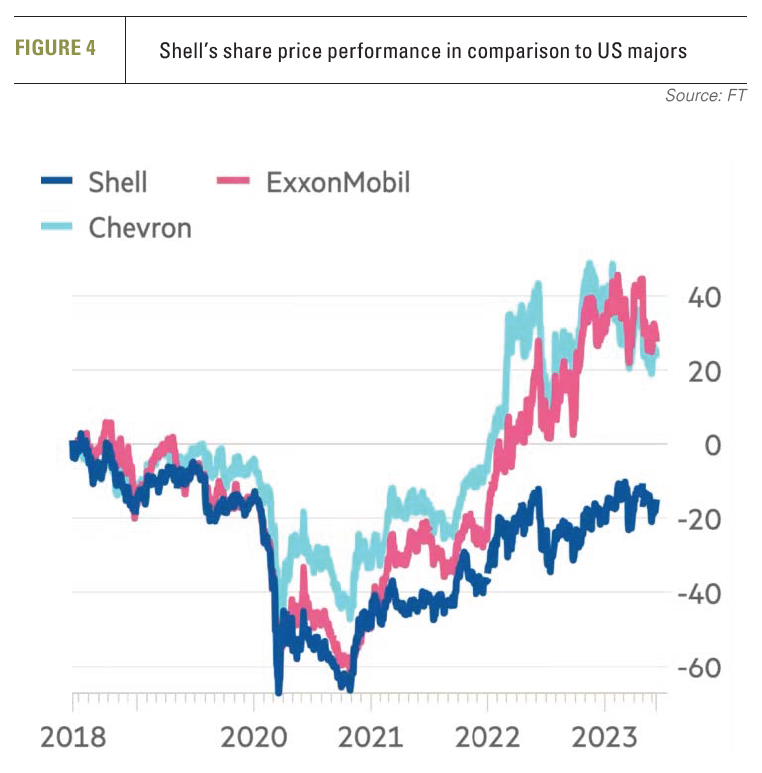

Shell’s CEO said: “we will invest in the models that work – those with the highest returns that play to our strengths." He added “It is critical that we avoid dismantling the current energy system faster than we are able to build the clean energy system of the future.” He is determined to take actions to close Shell’s valuation and share price performance gap with the US majors (see figure 4). Over 2018-2023, the gap widened. ExxonMobil and Chevron’s share price increased by about 30%, while Shell’s actually declined by about 20%.

Shell’s CEO said: “we will invest in the models that work – those with the highest returns that play to our strengths." He added “It is critical that we avoid dismantling the current energy system faster than we are able to build the clean energy system of the future.” He is determined to take actions to close Shell’s valuation and share price performance gap with the US majors (see figure 4). Over 2018-2023, the gap widened. ExxonMobil and Chevron’s share price increased by about 30%, while Shell’s actually declined by about 20%.

Facing criticism that it was shifting away from oil and gas at a time of booming prices, while returns from its low-carbon businesses remained poor, recently Shell scrapped a number of green projects, including in offshore wind, hydrogen and biofuels, due to projections of weak returns. Sawan promised a “ruthless” focus on financial performance. “Ultimately what we need to do is to be able to generate long-term value for our shareholders.”

TotalEnergies, meanwhile, will be focusing on LNG after a very profitable year. Its CEO Patrick Pouyanne referred to LNG as a “pillar of TotalEnergies’ growth in the future.”

Clearly, what prompted the European majors to step back from their energy transition commitments are the high profits from their oil and gas operations and the low returns from their clean energy investments. Given the resulting bounce in their share prices, their investors appear to support this change of direction. Their new driver is “more value, with less emissions.”

The future

As the world moves towards clean energy, new technology advances will eventually render traditional energy companies that resist change obsolete. That was the warning from Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at the University of Oxford, who said “these companies, in the end, will die.”

In the longer term, survival will require transition beyond oil and gas and that requires maintaining a balance between traditional business and investing in low-carbon energy, which could eventually lead to increasing convergence between the majors. But with the speed of transition uncertain and with most outlooks showing oil and gas still needed in substantial quantities well into the 2040s – and probably beyond – that future is some way off.

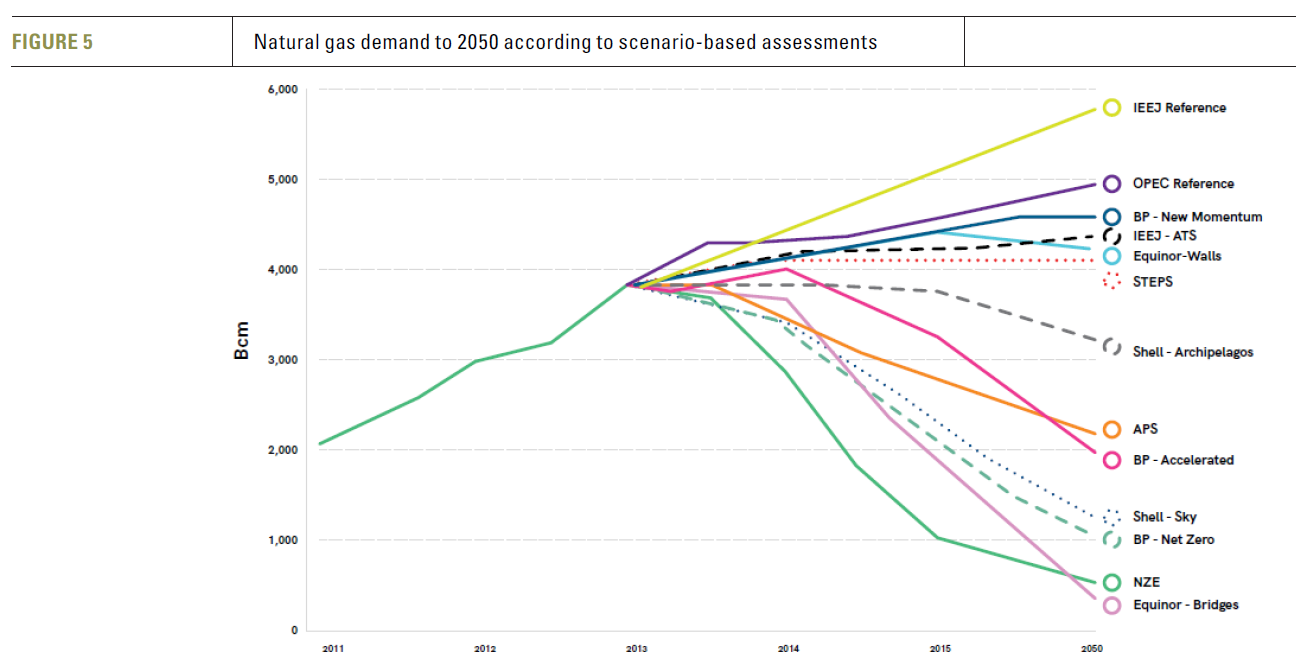

Outlooks that forecast how energy could evolve if current trends and known policies continue, without prescribing an outcome, show gas demand by 2050 mostly to grow, varying in the range 3.5 trillion m3 to 6 trillion m3 (see figure 5).

However, in a very uncertain energy world, should development of clean energy technology progress faster, there could still be a real threat of declining oil and gas demand beyond the next decade. As a result, as Wood Mackenzie points out, investment priority in oil and gas will continue to be in “low-cost, short-cycle, fast-payback projects with a below-average emissions footprint.”

In the meanwhile, in the US the incentives provided by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) may yet push the US oil majors to accelerate low-carbon project investment.

One thing is certain: as long as demand for oil and gas persists, there will be companies happy to meet it. Forcing majors out of that is not the solution. National oil companies will step in to fill the gap. What is needed is to bring oil and gas demand down and that is for governments to do, through appropriate policy measures – it is not the role of the majors.

In an era of increasing volatility, the challenge for majors – US or European - is to protect financial performance, while preparing for the inevitability of energy transition, in a world where there is great uncertainty about “what the energy system of the future is going to look like.”

The majors can play a vital role in supporting global energy security. But realising this potential requires overcoming environmental concerns and especially methane emissions across the entire LNG value chain. With EU imports of US LNG skyrocketing, and with the coming of new EU and US regulations, the industry needs to accelerate such efforts. The availability of improved technology and stricter monitoring hopefully will reduce methane leakages and emissions to acceptable levels within this decade. As long as such emissions persist, they will continue to undercut the role of LNG as a cleaner fuel.