Dili to go it alone in high stakes gamble [LNG Condensed]

In August, Timor-Leste – formerly known as East Timor – celebrated the 20th anniversary of the referendum that paved the way to independence from Indonesia, yet its economic future looks very uncertain. Although the country produces high quality coffee and has the potential to become a significant tourist destination, its short-term economic prospects are almost entirely dependent on the oil and gas sector in general and the Greater Sunrise LNG project in particular. Yet the government in Dili has adopted a high risk strategy to maximise the scheme’s benefits.

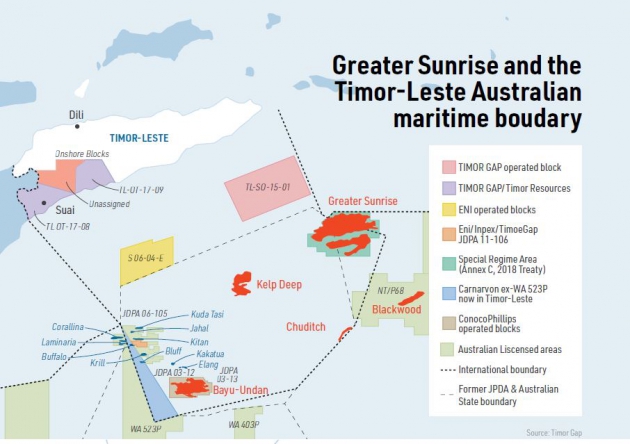

Timor-Leste already plays a role in the global LNG sector because gas from ConocoPhillips’ Bayu Undan gas-condensate field has been piped south to the US firm’s Darwin LNG project in Australia’s Northern Territory since 2006. Dili has earned more than $20bn from the project to date, making it by far its biggest source of revenue. However, production on the field is due to end in 2022 or 2023, so Timor-Leste is banking on Greater Sunrise to fill the huge gap that will appear in its revenues.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

The project has the potential to generate even more income that Bayu Undan. State-owned oil company Timor Gap forecasts $28bn in revenues from Greater Sunrise, based on an average oil price of $62.5/barrel, but some sources put the figure much higher.

Boundary agreement

One of the biggest obstacles to the project’s development was the lack of boundary delimitation between Timor-Leste and Australia relating to the project area. However, in March 2018, the two governments finally reached an agreement on the dispute that largely recognised Dili’s claim.

Relations between the two countries were badly affected by the drawn out negotiations, with Canberra accused of bullying its tiny neighbour into submission. It has been claimed – including by an Australian whistle blowing agent, who is now on trial in Australia – that Canberra used agents to spy on Timorese officials during the talks.

The delimitation agreement was finally ratified by Australia in August. The fact that it took Canberra 17 months to do so allowed the Australian government to continue drawing the 10% share of Bayu Undan revenues due to it while the field was still deemed to lie within the Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) shared by Australia and Timor-Leste.

The agreement required ConocoPhillips to conclude a new production sharing contract covering Bayu Undan with the government of Timor-Leste. Canberra has already received $5bn in revenue from Bayu Undan, according to Timorese sources.

Over the past year, Canberra has sought to undo some of the diplomatic damage caused by the spying revelations, including via an aid package that includes upgrading a naval base and helping to provide high-speed internet access in the country.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison attended the anniversary celebrations in August, and Canberra is also worried by growing Chinese influence over Timor-Leste.

Where to locate the plant?

However, the other main obstacle to developing Greater Sunrise has still not been overcome.

The consortium behind the project, which originally comprised ConocoPhillips, Osaka Gas, Shell and Woodside, wanted to liquefy the gas in Australia or possibly via a floating LNG plant. The most obvious option was to replace Bayu Undan in supplying Darwin LNG, making use of existing infrastructure.

However, successive governments in Timor-Leste have insisted that the gas be piped onshore onto their territory and hope to oversee the construction of an LNG plant at Beaço, on the south coast of Timor. Dili, which has already spent $100mn in financing the feasibility study into the Beaço plant, wants the industrial development and skilled employment that the project could bring. At present, few Timorese have the skills and experience needed to take up skilled posts on the project, although jobs in catering and security will also be on offer.

It is intended that the LNG plant will form part of the Tasi Mane industrial area, which the government hopes will include a petrochemical plant and oil refinery. However, there are big engineering challenges in piping the gas onshore to Timor because any pipeline would have to cross the 3,300m deep Timor Trough, which lies between the gas fields and the island.

The FID could be affected by ConocoPhillips’ decision in October to sell its operations in Timor-Leste and the Northern Territory, including Darwin LNG and the Barossa and Bayu-Undan fields, to Santos for $1.4bn. Santos plans to partly finance the deal by selling 25% of the Darwin LNG stake to South Korea’s SK E&S.

New consortium

Dili’s insistence on domestic liquefaction prompted ConocoPhillips and Shell to sell their stakes in the project consortium to the Timor-Leste government, which paid $350mn for ConocoPhillips’ 30% stake and $300mn for Shell’s 26.6% share.

This has left the government of Timor-Leste with a 56.6% stake in the project, with the remaining equity held by Australia’s Woodside Petroleum (33.4%) and Japan’s Osaka Gas (10%). Dili was to have received 80% of the profits from the project if the plant were built in Australia, falling to 70% if a Timorese site were chosen. The 10% difference was designed to compensate whichever side failed to secure the industrial capacity and employment the project would bring.

It has been widely reported in Australia that Woodside will only invest in field development, forcing Dili to finance the development of the LNG plant and pipeline itself. Woodside chief executive Peter Coleman has said that the separation of upstream and liquefaction ownership, as employed in Indonesia and Malaysia, would work “quite effectively”.

Financing the project

The government has no experience of building and operating an LNG plant, although it could seek out a non-equity operating partner, but the biggest problem will be securing the necessary investment. Some government officials have said that its sovereign wealth fund, the Petroleum Fund, cannot be tapped to provide this investment. It was set up to ensure that the country benefitted from Bayu Undan in the long run and accounts for 95% of government income. However, the same promise was also made over not using it to finance the purchase of the Shell and Conoco-Phillips stakes in Greater Sunrise, but this is where the money came from.

Even under the most optimistic timetable, production on Bayu Undan is expected to come to an end before Greater Sunrise comes on stream, so the Petroleum Fund – which contained $15.8bn at the end of 2018 – will be needed to bridge the gap in government finances over the intervening period. Given that the Fund will be exhausted in any case if Greater Sunrise is never developed, it is easy to see why some officials want to use it to finance the project.

Banks and other international lenders are likely to be reluctant to provide the required finance in the absence of an experienced LNG developer, leaving China as by far the most likely source of funding. Beijing is certainly interested in the country, having funded the construction of many projects, including the $490mn port at Tibar Bay, which is being built by China Harbour Engineering.

The port project is certainly expensive and as its container handling capacity is unlikely to be needed for many years to come, Beijing’s motivation can be seen as geostrategic rather than commercial, fitting in with its Belt and Road Initiative.

The investment required on Greater Sunrise is of a different order, but one Chinese company is already involved in the project. Timor Gap awarded state-owned China Civil Engineering Construction a $943mn contract to build the LNG offloading terminal at the Beaço LNG plant in April.

Beijing’s ambassador to East Timor, Xiao Jianguo, has described Dili’s economic strategy as “highly compatible” with the Belt and Road Initiative.

Moreover, Beijing could improve its energy security by funding the scheme. China’s LNG demand is rising quickly, from 37.8mn mt/yr in 2017 to 54mn mt/yr last year, making it the second largest national market for LNG behind Japan. China will have re-gasification capacity of 80mn mt/yr by the end of 2020, just 3mn mt/yr below Japan’s imports in 2018. Financing LNG projects directly would give Beijing more control over its supply base.

Timorese officials denied press reports in June that China’s Export-Import (Exim) Bank has already agreed to lend Dili $16bn to finance Greater Sunrise. Timorese Foreign Minister Dionísio da Costa Babo Soares said that the government needed just $12bn in any case and insisted that China was just one possible source of financing.

He said that the government is currently assessing funding options that would not jeopardise the economy, including from Australia, Europe, the US, China and the rest of Asia. In August, he said that the Exim Bank claims were a hoax “blown up by politically motivated people around the region”.

Looking for an LNG sunrise

The delimitation agreement with Australia allowed the government to launch a new licensing round in October, with eleven offshore and seven onshore blocks on offer. All bids are to be submitted by next October, with the successful companies announced next December. Seven-year licenses are on offer. There will be no signature bonuses, but there will be minimum local content requirements and profits are to be divided 60:40 between investors and the government.

Timor Gap wants to take the FID on Greater Sunrise by the end of next year, with first gas in 2026, but this is dependent on securing financing.

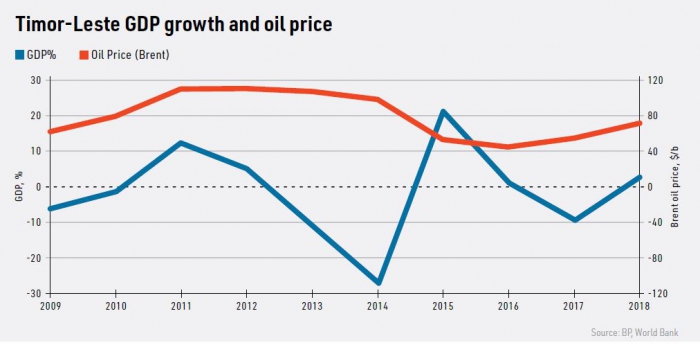

The government is under pressure to ensure that the project is developed quickly because its economic fortunes over the next decade depend on it. National infrastructure remains limited, not least because of the impact of the Indonesian occupation and independence war from 1975.

The public spending deficit reached a huge 19% of GDP in 2017 because of the lack of other revenue streams. Three other hydrocarbon fields in territory now regarded as Timorese – Bufallo, Laminaria and Coralina – have already been exhausted.

Timor-Leste is one of the most oil and gas-dependent countries in the world. The government’s gamble may pay off, if Greater Sunrise is developed, but if not then the country is in for a rough ride unless it can develop other forms of income.

Available Exclusively to NGW Subscribers:

Volume 1, Issue 12 - January 6, 2020

|

LNG Condensed brings you independent analysis of the LNG world's rapidly evolving markets. Covering the length of the LNG value chain and the breadth of this global industry, it will inform, provoke and enrich your decision making. Published monthly, LNG Condensed provides original content on industry developments by the leading editorial team from Natural Gas World. LNG Condensed is your magazine for the fuel of the future. Sign up to NGW Basic FREE or to NGW Premium now to receive LNG Condensed monthly (you will find every issue of LNG Condensed in your subscriber dashboard)

|

In this Issue:Editorial: Climate Resilience There were many major achievements for the LNG industry over the course of 2019. Final investment decisions were taken on a swathe of next generation LNG projects in Russia, Mozambique, Qatar and the US. Even Nigeria LNG’s long overdue expansion got the go-ahead. There was clear evidence of the LNG market’s growing maturity in the form of the steep rise in liquidity in futures contracts linked to S&P Platts JKM price assessment, while BP’s publication of its LNG trading terms and conditions should aid much-needed contract standardisation. The growth of portfolio players, more diverse pricing mechanisms and the gradual disappearance of destination restrictions all bode well for increased international LNG trade. The LNG industry is booming, but is it ready for climate change? The LNG industry is set for continued, rapid expansion. As growing gas use now outweighs the emissions benefits of reduced coal consumption, and renewables are increasingly competitive, the environmental and economic case for LNG is eroding. Companies need to take a hard look at their business models and make radical changes – otherwise their image will quickly move from being part of the solution to being part of the climate change problem. Dili to go it alone in high stakes gamble The government of Timor-Leste has bought out foreign partners in the planned Greater Sunrise project to ensure the scheme’s LNG plant is built on domestic soil, but raising the fi nance for development is unlikely to be easy. Meanwhile, gas is running out on the Bayu Undan field, on which Dili is heavily dependent for state income. North Asian nuclear trends: implications for LNG North Asia accounts for a quarter of operational nuclear capacity worldwide, and about two-fifths of the capacity under construction or planned. But the prospects for nuclear power in the region vary widely, as do the implications for LNG requirements. Country Focus: Bangladesh’s LNG demand prospects Bangladesh is a newcomer to the world of LNG, but promises to become a substantial market with imports reaching 30mn mt/yr by 2041. Yet it would be foolhardy to say this demand is set in stone. Actual consumption depends on an ambitious industrialisation strategy and infrastructure delivery in all areas which could both benefit and detract from LNG demand. Project Focus: Rio Grande LNG US company Next Decade could hit the headlines early in 2020 if, as billed, it takes a final investment decision (FID) on its Rio Grande LNG project, the largest of four US LNG plants to receive final approval in November from the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (Ferc). Rio Grande LNG is located at the relatively uncongested Brownsville deepwater port on the US Gulf Coast. Technology Focus: FRSUs - The LNG industry’s flexible friend The growing popularity of floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) is an integral part of the LNG market’s increasing flexibility. |

|---|