Country-Focus: Vietnam - Capital Mobilisation Challenges [LNG Condensed]

Vietnam’s Gas Master Plan (GMP) envisages gas demand rising from about 10bn m3 today to about 30bn m3 by 2035. The country has two major gas projects in development, as well as a number of smaller prospects, but, even so, a World Bank report published in December estimated that by 2035 more than half Vietnamese gas demand will be met by LNG.

According to consultants Wood Mackenzie, both central government-sponsored LNG projects under the GMP are progressing alongside a number of private-sector led projects in conjunction with local government. However, not all will be built and the key to successful project development, given the focus on power supply, will be downstream gas plant operators agreeing bankable power purchase agreements with state electricity company EVN.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

DOMESTIC GAS SECTOR

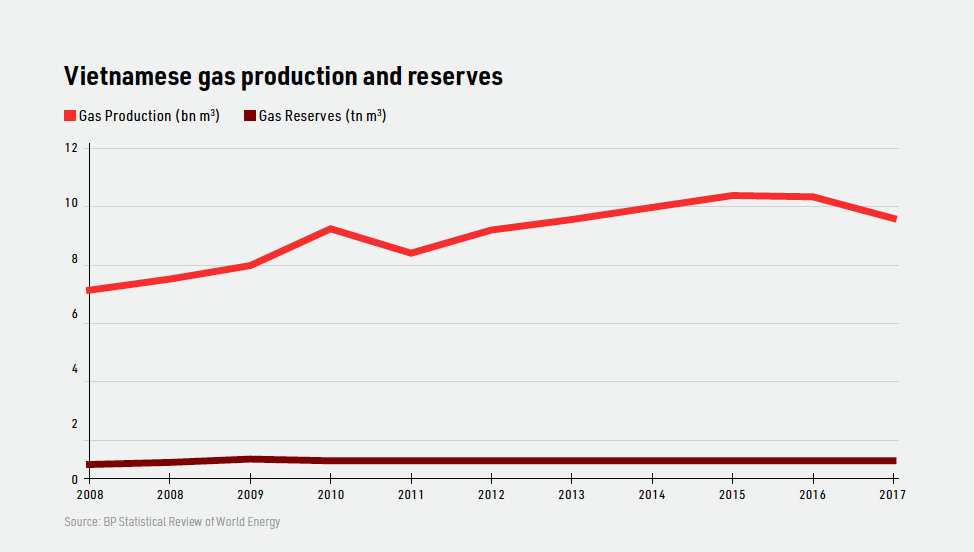

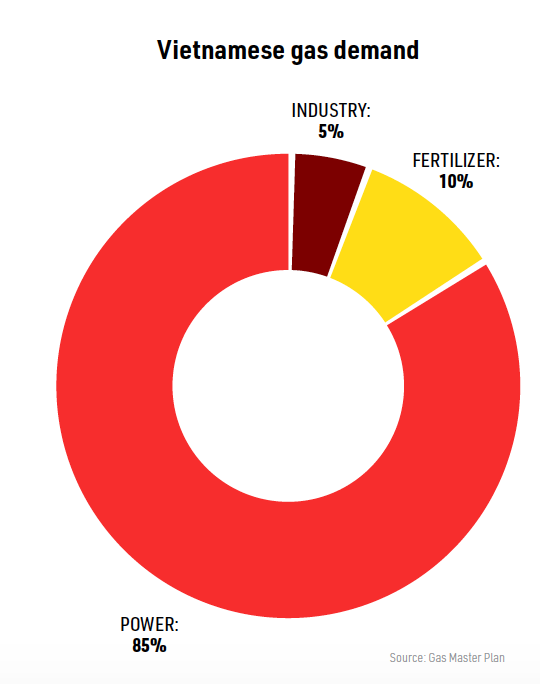

Electricity generation accounts for 85% of Vietnamese gas demand, with the remainder made up by fertilizer production (10%) and industrial demand (5%). Domestic gas production peaked at 10.2bn m3 in 2015. According to the Office of General Statistics, estimated gas production in 2018 was just short of 10bn m3, up 1.1% on 2017. PetroVietnam reported natural gas output of 1.66bn m3 in January-February. However, depletion from old fields has led to forecasts of a sharp fall in output from 2020.

Sustaining the country’s gas production into the 2020s depends heavily on the development of two major projects.

The Block B – O Mon gas development is already delayed, following disagreement between US major Chevron and PetroVietnam over gas prices. PetroVietnam subsequently took over Chevron’s stake in the project and now holds a 69.67% interest in the offshore Block B fields, with Japan’s Mitsui holding 22.59% and Thailand’s PTTEP 7.74%.

The project requires upstream development of fields in the Malay-Tho Chu basin and construction of a pipeline which will supply gas to new power plants being built in Vietnam’s south. Recoverable gas reserves were initially estimated at 107bn m3 and the project is expected to produce 5bn m3/yr. According to WoodMac, if both upstream and downstream elements of the project progress in a timely fashion, the Kim Long to O Mon pipeline will be commissioned in late 2023.

The second major project is Ca Voi Xanh, which is being developed by US major ExxonMobil. Located in the shallow waters of block 118, the field is Vietnam’s largest gas discovery to date. The field will supply gas to four generation units with total capacity of 3 GW. WoodMac estimates that the power plants should be commissioned between 2023 and 2024. A gas sales agreement has been reached between ExxonMobil and state oil company PetroVietnam and a front-end engineering and design contract was issued to Italy’s Saipem in February.

However, a final investment decision on the project is not expected until next year. Ca Voi Xanh reserves are estimated at 150bn m3, and output is expected to reach 9bn m3/yr.

If these projects progress on schedule, Vietnam should see a surge in gas production between 2023-25, but at the same time a jump in gas demand, as the two biggest projects are both tied to new downstream gas-fired generation projects.

LNG PLANS

PetroVietnam Gas forecasts a shortfall in domestic gas supply of over 2bn m3/yr in 2023 rising to 7bn m3/yr by 2030. To meet this deficit, PetroVietnam is developing a 1mn mt/yr LNG import terminal at Thi Vai, which is expected to fuel 1.5 GW of gas-fired power plant. The project is expected online in 2020/21 and may be expanded to 3mn mt/yr by 2025. A second LNG terminal is being considered at Son My, which could be in operation around 2023-25.

In addition, downstream oil company Petrolimex (formerly Vietnam National Petroleum Company) is looking at building an LNG terminal in the southern coastal province of Khan Hoa, with the intention of supplying gas to as much as 6 GW of gas plant built by EVN. This project is intended for completion in the late 2020s. Reports indicate that up to 10 Vietnamese LNG import projects, almost all LNG-to-power, have been floated by international and domestic companies.

The GMP envisages 3 to 4 LNG terminals being built in the period 2021-2025, each with capacity of 1-3mn mt/yr, mainly in southern Vietnam. In 2026-2035, a further 5-6 terminals are planned each with capacity of 3mn mt/yr. LNG imports are expected to begin in 2021 and reach 5mn mt/yr by 2025, 10mn mt/yr by 2030 and 15mn mt/yr by 2035.

CAPITAL MOBILISATION

The World Bank warns that the need to attract large-scale investment is exposing the country’s gas market structure and pricing regime. PetroVietnam has a monopoly on mid-stream infrastructure and gas pricing is “based on bilateral negotiations referencing low-cost fields developed prior to 2007,” according to the bank, which continued, “a comprehensive gas liberalisation and PetroVietnam restructuring strategy is needed for development of the domestic gas market.”

The bank points to a number of major constraints retarding the mobilisation of foreign capital in the country’s energy sector. These include an ambiguous and changing legal framework, inappropriate risk allocation (affecting renewable energy development in particular), the lack of clear government policy on supports for gas and electricity projects, continuing concerns over currency convertibility, and the risks imposed by potential misalignment of gas and electricity policy, given that gas developments are so dependent on the electricity sector to provide demand.

The World Bank estimates that cumulative gas sector investments, including in LNG infrastructure, will need to total $20bn for the period 2015-2035. Mobilising this capital will be a challenge. Capital availability and foreign investors’ risk appetites may prove a key determining factor in how closely outcomes resemble the electricity sector projections laid down by the country’s planners.

.png)

Vietnam’s economic growth and rising living standards mean less concessional funding is available to its state companies. In addition, state debt levels are already close to the government’s cap of 65% of gross national product, implying that Vietnam will increasingly have to look to foreign debt and capital markets, as well as foreign industrial partners to expand its energy industries. This, in turn, suggests that any delays in restructuring and deregulating its power and gas sectors will have knock-on implications for foreign companies’ willingness to invest in the country.

_f300x424_1560320133.jpg)