Country focus: Slow progress on LNG and renewables bode ill for Italy [Gas in Transition]

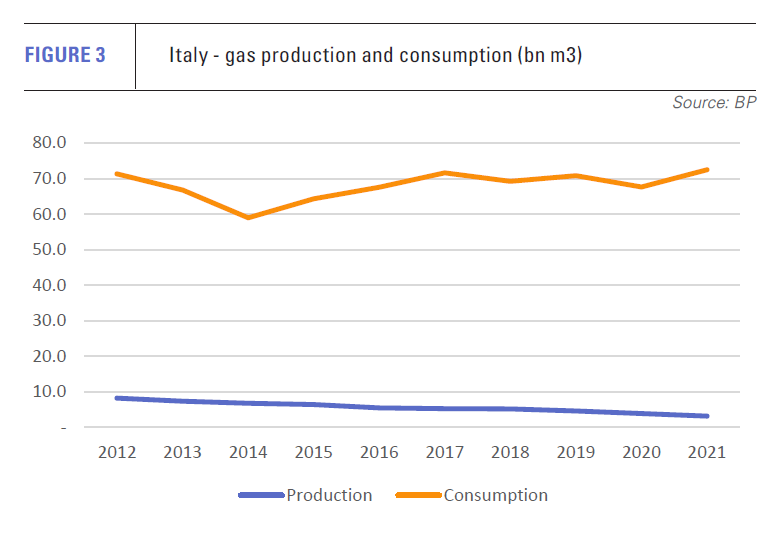

Italy is one of the most gas-dependent countries in Europe, and, until recently, one of the most dependent on Russian gas imports. In 2021, Italy consumed 75.88bn m3 of gas, of which 72.54bn m3 was imported. Russian gas accounted for 38.3% of total consumption and 40.1% of imports.

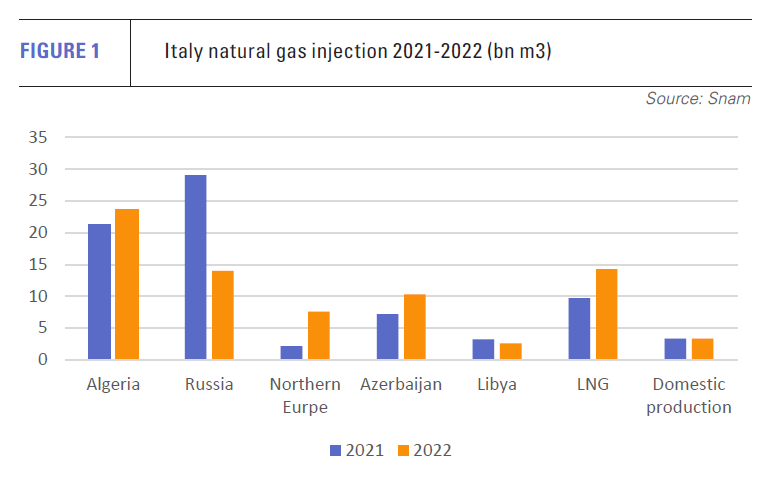

The country’s import slate changed substantially in 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and will change further this year. Russian gas imports plummeted to 13.99bn m3 last year, while pipeline imports from northern Europe, Algeria and Azerbaijan all rose.

While total gas system injections remained on a level similar to 2021 (see figure 1), consumption fell by 10% to 68.7bn m3, according to data from Snam, the country’s gas transmission system operator. This allowed a substantial build in gas stocks, which ended 2022 at 84% full in comparison with 68% at the end of 2021.

High prices, warm weather and conservation efforts led to a 16% fall in residential and commercial consumption, a 14% drop in industrial gas demand and a 3% fall in gas-for-power use.

However, Russian gas imports to Europe this year are far lower than in 2022. In first-quarter 2023, they were running at about 500mn m3 a week, around a quarter of the average for first-quarter 2022, and almost all via the southern TurkStream pipeline, according to the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. In contrast, Russian gas imports only fell to current levels by week 37 of last year.

An increase in non-Russian northern gas transits, which rose from 2.17bn m3 in 2021 to 7.58bn m3 last year, were an important component of Italy’s increase in non-Russian gas imports. Despite the substantial gains in LNG import capacity in northern Europe, lower Russian imports all year this year suggest Italy may struggle to import as much additional gas from the north in 2023.

LNG capacity increase important but insufficient

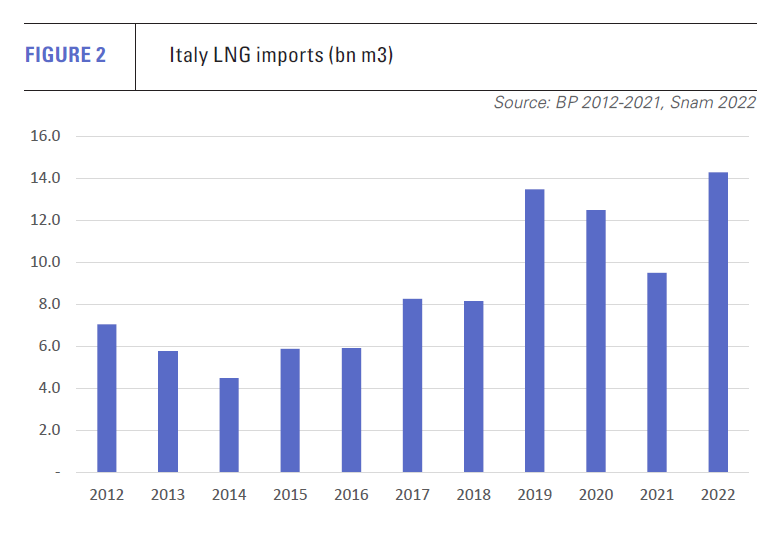

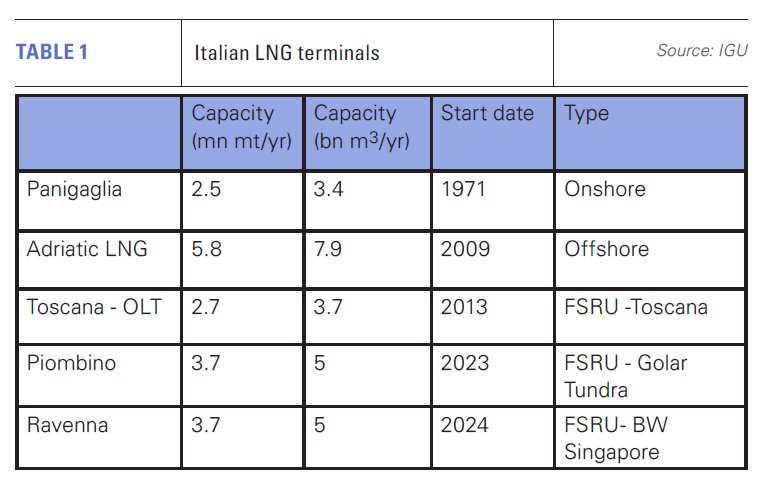

Italy has three LNG terminals with total nameplate capacity of 14.96bn m3/yr. In 2019 and 2020, the three terminals were operating fairly close to full capacity, but this dropped in 2021, particularly in the second half as LNG spot prices rose to high levels.

In 2022, despite prices remaining elevated, LNG regasification rates were ramped up to help address the shortfall in Russian gas volumes, resulting in a record level of LNG imports (see figure 2). This has continued into 2023. In week 13 of this year, Italy’s regasification capacity was operating at 93%, compared with an average of 79% in the period 2019-2021.

Italy did not have the same level of spare capacity as northern Europe or the Iberian Peninsula heading into the crisis, and projects to increase LNG import capacity are lagging in comparison. So far, no new LNG import capacity has come onstream. Of two planned projects, both Floating Storage and regasification units (FSRUs), only one will start operating this year.

Snam bought two FSRUs last year and expects to have the first, the Golar Tundra, in operation at Piombino in Tuscany by early May. The vessel, which cost $350mn, arrived in late March. The FSRU has regasification capacity of 5bn m3/yr and 37 of a total of 43 slots have already been allocated for a 20-year period from 2023/24 through 2043/44, according to Snam.

The second vessel, the BW Singapore, was bought for $400mn and also has regasification capacity of 5bn m3/yr. However, it is under contract to Egypt’s Egas until November and is currently located in the Red Sea at the port of Ain Sukhna. When the sale agreement was announced, the timeline for a start to operations in Italy was given as third-quarter 2024, owing to the need to finalise authorisation and regulatory processes, as well as complete works required for the mooring of the vessel and install a gas transmission network connection.

Pipeline gas supplies limited in the short-term

Italy has a well-diversified gas import system with pipeline links to other European countries in the north, as well as Azerbaijan, Libya and Algeria, which explains in part why it was not pursuing with any great rapidity new LNG import projects prior to the Ukraine crisis.

However, the ability of those connections to provide large volumes of additional gas in the short term is limited.

Algerian gas supply to Europe fell overall last year, but Italy managed to attract a larger share of the available gas. Its imports of Algerian pipeline gas rose from 21.17bn m3 in 2021 to 23.56bn m3 in 2022.

There is sufficient spare capacity on the TransMed pipeline to support further increases, but only if Algeria can supply the extra gas. Italian oil and gas major Eni has contracted to receive an additional 9bn m3 over the whole of 2023 from Algeria, 7bn m3 of which is to be delivered in the 2023-24 heating season.

Italy could benefit from reduced Algerian pipeline gas flows to Spain, following the suspension of flows through the GME pipeline via Morocco, but it is not clear that spare capacity here can easily be redirected either to LNG exports or the TransMed pipeline system. In addition, new production agreements will take time to feed through into increased supply.

Algeria’s own rising domestic demand and the fall in gas exports in 2022 are not good omens. In total, Algerian gas exports fell from a record 54.6bn m3 in 2021 to 49.3bn m3 last year.

Likewise, Italy is seeking increased gas supplies via the Greenstream pipeline from Libya, which carries its own uncertainties and promises little in the short term. Eni this year signed an $8bn gas production agreement with Libya’s National Oil Company. The deal is designed to increase Libyan domestic supply and increase exports via the development of two offshore gas fields.

However, gas from the deal is not expected to come onstream until 2026. Moreover, this assumes that the plan is not derailed by Libya’s internal conflict. The country’s eastern-based parliament has rejected any deals struck with foreign governments by the rival authorities in Tripoli as illegitimate.

Imports of pipeline gas from Azerbaijan via the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline reached capacity last year with just over 10bn m3 delivered to Italy, up from 7.2bn m3 in 2021. Although discussions are underway between shareholders to double the pipeline’s capacity, this project would take years to be completed, if approved.

Domestic gas production has been in long-term decline, falling to just 3.34bn m3 in 2021 and 3.31 bn m3 in 2022 (see figure 3). The government has announced plans to raise this to 6bn m3 and has said it will authorise new offshore drilling in the Adriatic Sea. However, even if production doubles, this feat is unlikely to be achieved this year and will provide only a small amount of additional gas.

Gas-for-power demand

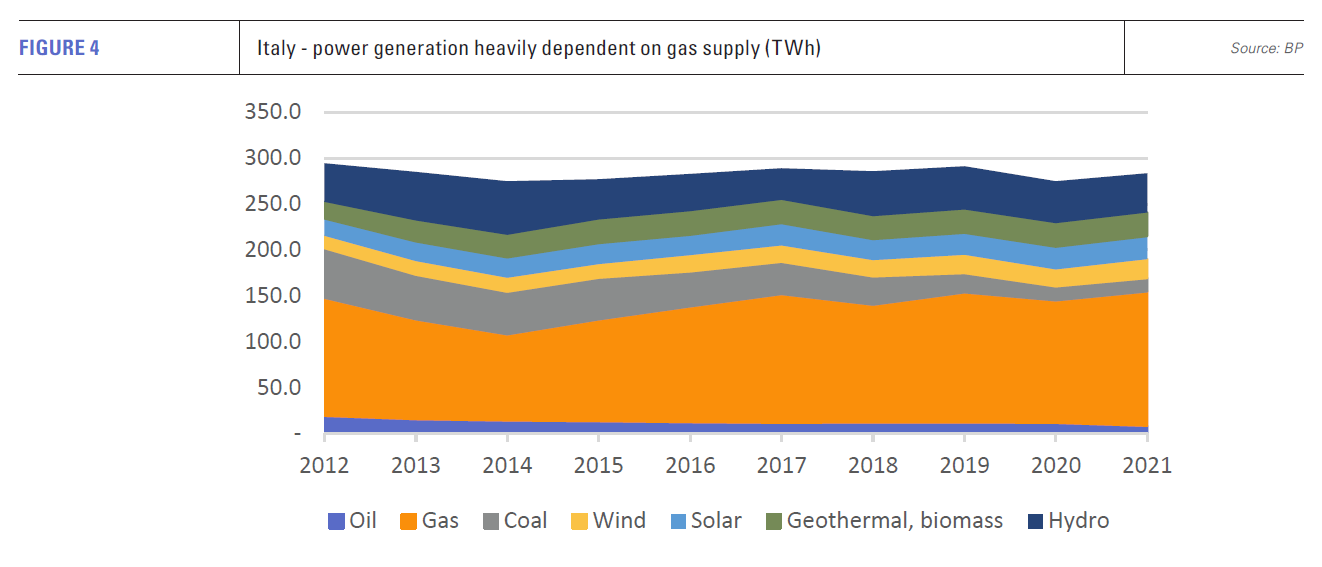

Gas consumption for power generation in Italy fell only marginally last year, despite high prices, reflecting the country’s high dependence on the fuel for electricity. In 2021, gas-fired generation accounted for 51.6% of domestically-generated power (see figure 4). Total electricity demand in 2022 was only 1% lower than in 2021 at 316.8 TWh, 13.6% of which was met by imports.

The second largest source of electricity generation in the country is hydroelectric power, but generation from this source plummeted 37.7% last year, as a result of drought, leading to a 6.1% increase in thermal generation, led by higher coal burn, as the government put the country’s coal phase-out plans into temporary reverse.

Wind power underperformed, falling 1.8%, as did geothermal, down 1.6%. Solar generation increased by 11.8%, but this translates into only about an additional 2.5 TWh of actual power.

Just as Italy has been slow to expand its LNG import capacity, it has been slow to deploy renewables and this oversight could tell this winter. Wind capacity at 11.8 GW at the end of 2022 has increased by less than 1 GW in three years and is way below the total installed capacities of other large European economies. Similarly, while solar power is expanding more quickly, the growth rate is unimpressive, running below that of Germany, France, Spain or Poland.

Drought remains a key factor

The drought suffered last year has continued, impacting northern Italy in particular. According to a report published in March by the Graz University of Technology in Austria, the situation has now become “very precarious”. Low rain and snowfall during the winter have not restored water levels.

The EU Joint Research Centre’s latest report on water security warned that Europe and the Mediterranean region could experience another extreme summer this year. The river basin of the Po, Italy’s longest river, saw its worst drought in 70 years in 2022 and its water levels remain well below the norm. Even the canals in Venice have dried up.

The prospects for a recovery in hydro generation this year look dim, while wind and solar will not add much generation, owing to the slow pace of new capacity additions.

As a result, increased gas supply by pipeline is vital to Italy’s energy security, but any uplift is heavily dependent on Algeria. A quick start to LNG imports in Piombino is therefore essential, but with the country’s existing LNG import facilities already working close to maximum capacity, an extra 5bn m3/yr of import capacity for three quarters of the year may prove too little too late.