Country Focus: Singapore’s LNG future [LNG Condensed]

To Singapore’s south, only 16 km at its narrowest across the Singapore Strait, lie the first islands of the giant Indonesian archipelago. Wedged between LNG producers to its north and south, and with only limited domestic demand and no gas production of its own, Singapore may appear at first glance an unlikely spot for an LNG hub. However, the continuous stream of vessels plying the Singapore Strait is a reminder that this city is the largest transhipment port in the world.

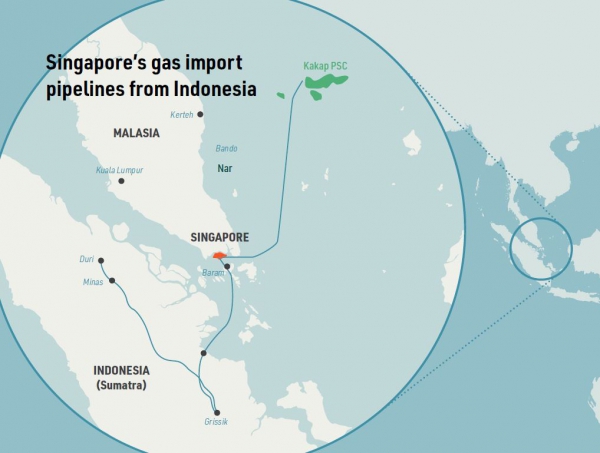

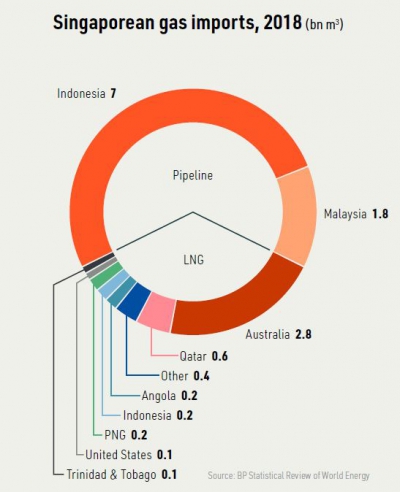

Currently, the country’s principal source of gas – the lifeblood of its electricity system -- is by pipeline from Indonesia, which exported 7bn m3 to Singapore in 2018. Pipeline imports from Malaysia amounted to 1.8bn m3, while domestic gas demand ran to 12.3bn m3 with the difference being made up by LNG imports.

Pipeline uncertainty

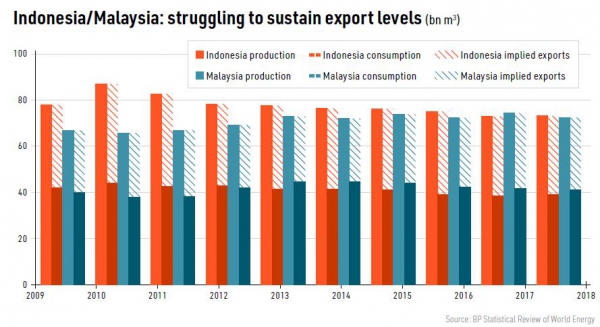

Indonesia and Malaysia have both become importers as well as exporters of LNG, recording imports of 3mn mt (4.1bn m3) and 1.4mn mt respectively in 2018.

In Indonesia, the Arun LNG facility was converted to a regasification terminal in 2015 to meet the deficit incurred by declining fields and fast rising demand in the country’s most densely-populated island Sumatra, which lies just across the straits from Singapore.

Moreover, on February 8, Indonesia’s energy and mineral resources ministry announced that it would stop shipments of gas to Singapore in 2023, confirming a similar statement made in November.

Instead of feeding into the Grissik-Batam-Singapore (GBS) export pipeline, gas from Indonesia’s Corridor Block will go into the domestic Dumai Duri transmission pipe, where it will be distributed to industrial estates in Sumatra. Singapore receives about 3bn m3/yr via the GBS pipeline, with the other 4bn m3/yr coming through the offshore West Natuna-Singapore subsea line.

The future of Malaysian gas imports and those from Indonesia’s West Natuna block is uncertain given both countries rising demand for their own gas, so Singapore is preparing for a future in which it may be completely dependent on LNG for its gas supplies.

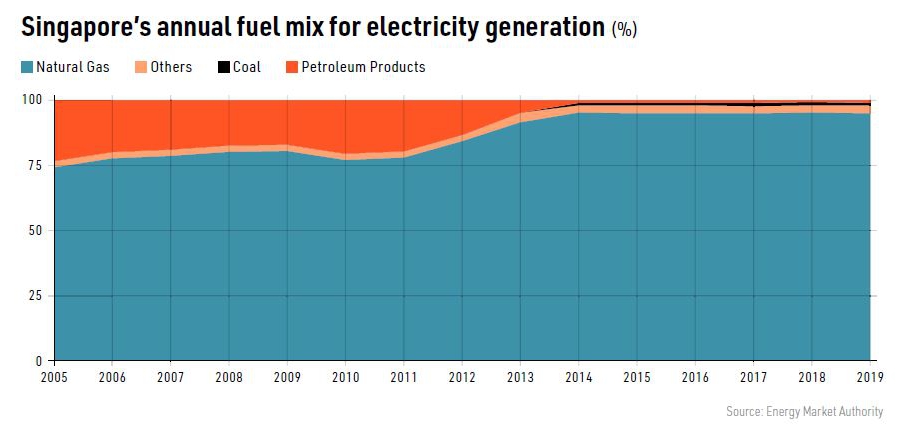

Given its lack of natural resources, small land area and large population, Singapore’s other energy options are very limited. It adopted a new target for solar power last year of 2 GW by 2030, but even this would only account for 4% of current electricity demand. Its energy mix for electricity generation was 95.3% dependent on gas in the first quarter of 2019, with the remainder made up by coal (1.2%), oil (0.7%) and others (2.9%), according to Singapore’s Energy Market Authority (EMA).

Future planning

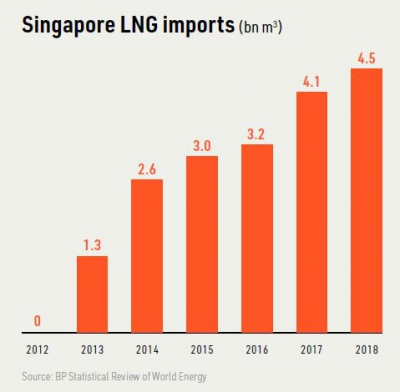

Concerned by the long-term reliability of its pipeline imports, Singapore built an LNG import terminal with capacity of 3.5mn mt/yr in 2013, expanding its capacity and storage in 2014 and then again in 2018. Singapore LNG’s (SLNG) Jurong terminal now boasts 11mn mt/yr regasification capacity and four storage tanks, more than enough to meet the country’s gas demand.

Singapore has so far not had to utilise the Jurong terminal’s full capacity, but the Indonesian decision on the GSB pipeline clearly indicates Singapore’s reliance on LNG will rise. Singapore received net imports of 2.56mn mt LNG in 2018 and re-exported 0.56mn mt, making it Asia’s largest re-exporter, with the reloaded cargoes finding their way into South Korea, China and Japan.

Singapore’s LNG ambitions go beyond energy security and aim to leverage its technological and financial advantages, building on its deregulated gas market, ship-building capabilities, its long-established role as an oil hub and broader IT and trading talents.

One key area is the lead Singapore has taken in providing LNG as bunker fuel for ships. Singapore has decided to provide for ship-owners who have picked LNG as the solution to the lower sulphur limit on shipping fuels this year. It has awarded bunker supply licences to state-owned Pavilion Gas and to FueLNG, a joint venture between Anglo-Dutch Shell and Singaporean ship builder Keppel. It has provided co-funding for new LNG-fuelled vessels and waived dues for harbour craft using LNG.

In December, Pavilion Energy announced a 10-year agreement with France’s Total to develop bunkering supply facilities, having earlier in the year chartered a new build bunker vessel from Japan’s Mitsui OSK Lines, which is being built at Sembcorp Marine’s Tuas Boulevard shipyard.

Meanwhile, Keppel Offshore and Marine shipyard is busy constructing a 7,500m3 LNG bunkering vessel for FueLNG, which is expected to be operational this year.

Building demand

Bunkering is one element of building new demand for LNG, but Singapore is also looking to break bulk big shipments so that smaller vessels can reach areas in southeast Asia without the infrastructure large LNG vessels need.

SLNG last year completed modifications to the secondary jetty at its LNG terminal to allow the reception and reloading of small LNG ships of between 2000 m3 and 10,000 m3 capacity. These will be able to reach remote power plants and islands. The first small-scale LNG reload was carried out by SLNG in June 2018 for the 6,500 m3 vessel Cardissa.

On the back of the expected growth in its own LNG demand, ship bunkering and small-scale LNG, Singapore hopes to recreate the same success with LNG that it has had as an oil trading and shipping centre, potentially becoming a key LNG pricing point and hosting the financial architecture required to facilitate trading in LNG.

In this it faces competition as both Japan and China have ambitions to establish regional pricing points. Both offer larger domestic gas markets, but Singapore is anglophone and has a trusted regulatory system. It hopes that its well-developed financial system, favourable tax regime and lead in LNG bunkering and transhipment will see it become the hotspot of Asian LNG trade.