Part 2: Fracking to Reduce Risks: Bulgaria and Poland Redefine their Gas Dependency

Part one of Michael LaBelle's two part series

The ability to break away from dependency means redefining relationships. For shale gas this redefinition must include the economic, social and institutional advantages and disadvantageous. Environmental arguments are not the only element for acceptance or rejection. Gaining a greater understanding of the gas sector necessitates a broad risk analysis that captures various elements within complex historical relations and geographic positions.

This article is the second part of a two part series analyzing a spectrum of risks in Bulgaria and Poland. Concisely isolating and analyzing the dependency elements, and where these two countries gain the most from breaking away from the teat of Mother Russia, demonstrates the importance of domestically produced gas. Independence may be prized more by some – rather than all.

The analysis presented here draws from a recent report written for a special workshop on shale gas in Europe held by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs September 9, 2012. Drawing on 16 interviews conducted in Poland in August 2012 and a diversification assessment of Bulgaria, a full report on the short term – contractual risks, and the long term – governance risks, was produced. The report assessed the concerns of petitioners from Bulgaria and Poland; elevation of their concerns to a higher policy level also enables a broader perspective to be taken of the evolution and development of the shale gas sector in the two countries.

Risks

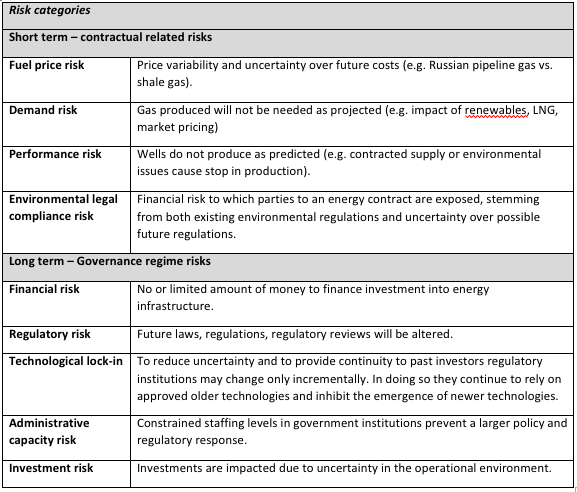

There are a range of risks that influence and impact the decision to invest and explore for shale gas using hydraulic fracturing technology (Table 2). These risks are highly relevant to how governments make decisions and impact the regulatory environment in a country. They also influence the activities of firms and business decisions (including technologies used). The environment is impacted by this decision-making process. This approach draws on a peer-reviewed risk typology previously developed to assess institutional efforts in the European Union to transition towards a low carbon economy by 2050.

|

|

Poland

The complexities within the story of Poland’s quest to develop shale gas provide a unique environment to apply a full risk analysis to the political, economic and social environment. The involvement of five state ministries, private and publically owned energy companies matched to social concerns, provides the backdrop to a deeper analysis. Exposed are a range of risks that show potential long-term benefits to Poland. The discussion below is framed around three key themes identified by the petitioners concerns, ‘institutional’, ‘environmental and technical’, and ‘financial’.

Institutional Risks

Institutional considerations, expressed by Polish petitioners, need to be assessed against the institutional environment in Poland. This does not require a comprehensive review of local, regional and national authorities. Rather, a top-down perspective of the apparatus of the state enables a perspective on the development of shale gas in Poland, extending from the center to the periphery.

The ability of administrative institutions to evolve as technology develops is essential. Petitioners’ concerns reflect a significant degree of concern that authorities should oversee the environmental impact of shale gas drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology. Stringent environmental assessments and the need for re-approval for altering drilling plans were cited as being clear examples of how the current oversight.

Self-regulation, may not always be the most effective, but is certainly an important element in the context of an infant Polish industry. A significant accident with any environmental damage threatens to shut down the industry. If environmental damage occurs due to either constrained government staffing levels, or the inability to provide effective oversight of hydraulic fracturing, public perception may turn against shale gas. The use of conventional technologies will continue to be favoured in Poland.

Amongst interviewees, the operations of the different ministries were most frequently identified as being the greatest institutional barrier. Greater coordination and the clarification of financial matters and a faster licence approval process were cited as ripe for improvement. Reviewing applications is an important function that can hinder or facilitate the review process. Re-approvals must be done if the original technical specifications are altered, thereby slowing down the drilling process. An expensive option when the rig and crew are in place. The split of responsibilities does not appear to affect the environmental review process, but it does affect the time that it takes for documents to be retuned and/or decisions to be made.

In various interviews it was expressed, because of the exploratory nature of recent drilling activity, greater latitude, or quicker decision making on the part of authorities, was needed. However, a contrasting perspective can be offered - current institutional arrangements and processes may indicate caution on the part of authorities.

Environmental and Technical

The main thrust of the petitioners’ concerns is focused on environmental risks. These can be addressed through a systemic analysis of the individual risk elements. It is important to remember that shale gas extraction practices can be shaped by environmental concerns. This is the make-or-break issue for shale gas technology. The main risks are the environmental compliance and performance risks, which are potential financial risks stemming from existing and future environmental regulations.

The environmental impact of shale gas exploration and exploitation is a significant concern of petitioners. The interviews conducted in Poland provided significant insight into how both shale gas drilling technology is used and how, for example, protected Natura 2000 areas may or may not be impacted when shale gas is extracted.

The environmental compliance risks are the top concern for both shale gas advocates and opponents. In theory, any environmental damage caused by the shale gas industry can be expected to increase the risk that companies will suffer financial losses - with the potential outcome that all extraction activity will be halted. This indicates the existence of performance risks, where operators are contractually obligated to provide supply but may not be able to meet their contractual obligations because of stoppages in work (if we obviously consider that the national authorities will ensure the full and efficient implementation of environmental law). Research conducted by Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute (PGI-NRI)[i] indicates there are already established monitoring practices that show awareness of the environmental risks of shale gas exploitation.

Carbon emissions and shale gas

Another substantial environmental consideration that must be considered are the CO2 emissions generated from both coal and shale gas. This was addressed in part one of this article, but is important to consider and contrast this larger issue with the immediate local environmental concerns: if gas is to partially replace coal in the country’s energy mix, then CO2 savings must be considered. Research commissioned by DG CLIMA provides a comparison of these potential savings.

Examining the lifecycle GHG emissions of shale gas and coal in power generation indicates that shale gas offers the potential for a 41% - 49% reduction in GHGs.[ii] However these assumptions are based on Russian, South African and South American coal. Analysis done using Polish coal indicates greater reductions in emissions are possible. Compared to Polish lignite coal, the CO2 savings created by using shale gas are 74% - 78%, while compared to hard coal CO2 avoided emissions of 70% -74% may be expected. Using a future power plant efficiency rate of 48% (as assumed in the DG CLIMA[iii] study) CO2 savings using shale gas rather than lignite coal are 59% - 64%, while compared to hard coal savings are 51% - 58%.

Local environmental and infrastructural impacts

The impact that the shale gas industry can have on local infrastructure and the environment (such as roads and fields) relates to the larger issue of the localized impact of the gas industry. Communities need to be made aware of the impact the gas industry will have. Experiences from the US do provide some information about what to expect and these have been both documented[iv] and experienced by local Polish officials. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs[v] has arranged study tours for local officials to the US and Canada to increase their understanding of the economic and environmental impacts of the shale gas industry. The industry and government are undergoing a phase of learning while the exploration phase of shale gas is occurring. As documented, local impacts are being assessed[vi] and revisions to laws and regulations may occur.

Financial

The financial and environmental concerns of the petitioners are expressed in relation to the environmental impacts that shale gas will have on the immediate environment, which may include decreases in income for business, citizens and the state. In the interviews conducted, and in further studies about the potential role of shale gas in the Polish economy[vii] it is stated that significant investment could be encouraged by the existence of a shale gas industry.

The broader economic impact is assessed in a study sponsored by PKN Orlean and carried out by the CASE Scientific Foundation.[viii] Three different growth scenarios are developed for the shale gas sector: 1) moderate; 2) increased foreign investment and 3) accelerated growth. The projection ranging out to 2025 foresees 27,000 direct jobs created in the accelerated scenario and 483,000 indirect jobs created. However, this would require the drilling of 305 wells annually and annual investment of USD 3.5 to 4 billion. This is all extremely optimistic at this point, based on the minimum amount of wells drilled and the operating speed of both companies and the Polish government.

Price risks

An increase in the price of energy is a concern that must be considered whether shale gas is extracted or not. When it is considered that gas produces lower CO2 emissions compared to coal, and that the Polish government may not increase its RES above 20% by 2050[ix] then gas must be considered a viable option for replacing coal for reasons of: a) its lower cost (if the ETS allowances are priced high to discourage coal use); b) its lower emissions and; c) the limited use of renewable energy.

Declining domestic production of conventional gas will result in Poland importing more gas from both the East and West. Domestically-sourced gas, as with the case now, offers a stable pricing structure. Shale gas is perceived to be able to replace the conventional gas price stability. This, however, is dependent on other factors such as extraction costs, market conditions and well performance. Further research is necessary to understand the impact of carbon pricing (ETS), Polish shale gas geology, extraction costs and how this may affect the price of shale gas versus coal in the electricity mix.

The dominant position of Gazprom on the Polish market may lead to increases in and maintenance of high gas prices (this has broader economic consequences). The use of either LNG or pipeline gas from Germany (or other neighboring countries) may impact gas prices in Poland – however, this impact will be minor compared to the dominance of Russian controlled gas. Therefore pricing levels will remain high if significant supply competition does not emerge.

Domestic gas infrastructure

Currently, the dominant position of coal on the Polish market and its low price means that gas cannot compete. This has created two problems, as indicated by various public authorities, and indicates the need to develop a competitive gas market in Poland. First, there is a lack of a networked infrastructure for gas fired power plants to draw on. Second, the regulated price and current monopolistic gas market creates no pricing signals for producers of gas. Because of the physically and legally restricted market for gas, even if gas is produced from shale, problems could be experienced bringing it to market. Interviewees and government officials expressed the view that market liberalization will occur along with planned investments into tangible infrastructure.

Bulgaria: Policy Risk Analysis

As reflected in the first part of this article, the cut-off of gas to Bulgaria and neighboring countries in the 2009 dispute between Russia and the Ukraine marked an important milestone for publicity and awareness of gas dependency. While previous gas disputes did not emerge as internationally significant, 2009 marked the beginning of a larger push to diversify gas routes for the Southeast and the Central European region. The opening of the Southern Corridor of transporting gas, either from Russia or via Turkey from more eastern sources, gained momentum.

The scars of the 2009 gas dispute between Russia and the Ukraine, when the flow of gas to Bulgaria was cut off, may have faded but the event underscores the role of energy diversification. Bulgaria remains wedded to Russian energy supplies and technology: rejecting shale gas as an alternative energy source raises both political and energy security issues. The Bulgarian parliament in 2012 overwhelmingly rejected the use of shale gas technology by imposing a moratorium on exploration and extraction. This decision was based on environmental grounds and backed by broad social agreement; although rejection of shale gas may have corresponded with other vested interests in the current gas system.

The importance of place was stated in part one of this article series: location, location and Russia are the key elements of energy security in Eastern Europe. In the realm of the gas sector, no country represents the importance of the new European gas geography than Bulgaria. The plethora of new gas projects, from transit pipelines of South Stream and Nabucco to off-shore gas deposits in the Black Sea combined with a greater regional interconnection of the gas network – pumped full of LNG, Bulgaria could have a liquid gas market (although this is certainly dependent on the interplay of domestic and international actors – if it is possible that other interests, besides environmental, derailed the shale gas industry in the country).

The 2012 ban on shale gas extraction means an alternative method, compared to the Polish case, needs to be deployed. Therefore, a brief assessment of the risks associated with the diversification options of gas supply is done. This analysis concentrates on the risks present with the diversification options.

Short term - Contractual related risks

Bulgaria’s reliance on Russian gas actually creates a risk regime that is stable in the short term. If the risks associated with contract fulfillment and environmental compliance in Bulgaria are considered, then piped gas is a good short term option (if the country does not find it imperative for other reasons to foster alternative supplies). In the case of Poland, for geopolitical and economic reasons, energy diversification is more strongly desirable than for Bulgaria. Although Bulgaria is taking steps to diversify, the connection with Russia remains strong. Assessing some of the key risks expose the following:

- Fuel price risk: The price of gas in Bulgaria is predictable and constant. However, the total reliance on Russia for gas imports, with no alternative available, means there is no price competition that enables Bulgaria to benefit from lower priced gas (compared to some domestic gas that is 40% cheaper).

- Performance risk: The biggest risk to Bulgaria from reliance on Russian gas is interruption of the contracted supplies.

- Environmental compliance risk: The direct environmental impact of current gas supplies contracted with Gazprom means there is little risk exposure to environmental regulatory changes. However, the environmental compliance risk for future gas and oil extraction projects which are currently under consideration in the Black Sea must consider the environmental risks that they pose for the region.

The imposition of the shale gas moratorium essentially cut short the debate that needs to occur about Bulgaria’s energy mix and the acceptable impact on society and nature. Therefore, future investors in energy projects should consider the role that society and the environment play in decision making in Bulgaria. If environmental arguments are the prime reason for the cancellation of shale gas exploration efforts in the country, then it can be assumed that other projects will be subject to similar public scrutiny of their environmental impacts. However, if under-the-radar politics and special interests influence the decision making process, then consideration must be given to better understanding this influential factor and how it interacts with environmental arguments.

Long term – Governance regime risks

- Financial risk: Project financing in Bulgaria for energy projects has a difficult history. Construction of the Belene Nuclear Power Plant was cancelled in 2012 and the high costs of financing Nabucco have already required help from the European Investment Bank.

- Regulatory risk: The energy regulatory environment in Bulgaria generally places pressure on investors. Lower than expected approved market prices in the electricity sector have created disputes between energy regulators and private investors.[x] The cancellation of Chevron’s shale gas exploration permit also indicates the existence of a shifting regulatory regime.

- Technological lock-in: The exclusion of shale gas technology from Bulgaria means only traditional forms of extraction are possible. However, it is hard to exclude the use of other new technologies from Bulgaria’s energy mix. Certainly, the use of nuclear power as a viable energy option and the deployment of solar and wind indicates that Bulgaria is a country willing to embrace new technologies. Therefore, even in the case of off-shore drilling in the Black Sea there are opportunities for the use of new technologies.

- Investment risk: The increase in gas diversification options for Bulgaria could lead to significant choice in gas projects. The exclusion of shale gas as a domestic source of gas, in the end, may not adversely affect the long term gas security of the country. If the proposed projects, like Nabucco, South Stream and greater interconnector capacity are built then Bulgaria could become significantly diversified to offer price competition and increased security of supply.

Conclusion

The development of shale gas in Poland and Bulgaria is proceeding along different paths. Justifications for its development in Poland differ from those used in Bulgaria. While the necessity exists for both countries to reduce the cost of gas and increase the security of supply, the two countries have chosen different paths.

Poland differs in its level of energy security due to its geographic proximity to Russia, its historical relations and its need to introduce cleaner energy sources. The dominance of coal in Poland’s electricity mix must be reduced for environmental reasons. The economic benefits – if shale gas can be extracted safely at reasonable prices - represents a significant opportunity for the country to reduce its dependence on imported gas while increasing the proportion of ‘lower carbon’ electricity.

Finally, energy security concerns in former Communist countries must be accounted for at the EU level. Environmental concerns over energy technologies need to be considered and accommodated. Yet, even considering this fact, it is essential when dealing with current environmental and security issues to consider the need to diversify away from using Russian sourced gas which has a monopolistic position in the energy markets of many new EU Member States. Shale gas is changing the global gas market and understanding how this can affect European - particularly Eastern European - energy security must be part of the debate.

Michael LaBelle is an Assistant Professor at the Central European University Business School and in the CEU Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy. He teaches courses on sustainability in business and on energy technologies and policies. He conducts research on how institutions and organizations foster change to contribute to a low carbon future. His blog is energyscee.com.

[i] Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute (PGI-NRI) in Warsaw, “Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny - PIB - Environmental Impact of Hydraulic Fracturing Treatment Performed on the ŁEBIEŃ LE-2H WELL”, n.d., http://www.pgi.gov.pl/en/archiwum-aktualnosci-instytutu/4087-aspekty-rodowiskowe-procesu-szczelinowania-hydraulicznego-wykonanego-w-otworze-ebie-le-2h.html.

[ii] AEA Technology, Climate Impact of Potential Shale Gas Production in the EU (European Commission DG CLIMA, July 30, 2012), 67, http://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/eccp/docs/120815_final_report_en.pdf.

[iii] AEA Technology, Climate Impact of Potential Shale Gas Production in the EU.

[iv] Susan Christopherson and Ned Rightor, “How Shale Gas Extraction Affects Drilling Localities: Lessons for Regional and City Policy Makers,” Journal of Town & City Management 2 (2012): 20.

[v] Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “In-person Interview”, September 19, 2012.

[vi] Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute (PGI-NRI) in Warsaw, “Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny - PIB - Environmental Impact of Hydraulic Fracturing Treatment Performed on the ŁEBIEŃ LE-2H WELL.”

[vii] Adam B. Czyzewski, Eduard Bodnari, and Grzegorz Kozieja, Gas (R)Evolution in Poland: Which Way to Success? (PKN Orlen, 2012).

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Władysław Mielczarski, “Prognozy Produkcji Energii Elektrycznej i Zużycia Paliw” (presented at the Economic Forum, Kyrnica-Zdroj, Poland, September 4, 2012).

[x] Michael LaBelle, “E.ON Gets Fed up and Disposes of E.ON Bulgaria,” Blog, Ww.energyscee.com, December 8, 2011, http://energyscee.com/2011/12/08/e-on-gets-fed-up-and-disposes-of-e-on-bulgaria/; Michael LaBelle and Vidmantas Jankauskas, “Electricity Post-Privatization: Initial Lessons Learned in South East Europe” (Regional Centre for Energy Policy Research, 2009), http://www.rekk.eu/images/stories/munkatarsak/mike/post_privatization_report_final.pdf.