Big finds will boost Middle Eastern LNG exports [LNG Condensed]

The United Arab Emirates’ role in global gas markets could change markedly as a result of two big discoveries earlier this year: the Mahani discovery onshore Sharjah and the Jebel Ali field on the border of Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The latter, in particular, will have profound implications for the balance of the country’s gas imports and exports. It could hasten the demise of Qatari gas exports to the UAE, creating more feedstock for Qatar’s own LNG capacity expansion, while also providing sufficient gas to justify the construction of new LNG export capacity in the UAE itself.

In January, Sharjah National Oil Corporation (SNOC) – the state oil company of Sharjah, one of the seven UAE emirates – announced that it and Italian oil and gas major Eni had made a new gas and condensate find on the Area B concession onshore Sharjah. The discovery tested at 50mn ft3/day, although no reserves estimate has been given. It is Sharjah’s first onshore gas discovery for 37 years.

SNOC had signed a contract with German firm Uniper in December 2017 to provide a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) for LNG imports, but has now decided to suspend the project, banking on the new find to provide the required power sector and industrial feedstock. SNOC, which had awarded front-end engineering design (FEED) and engineering procurement and construction (EPC) contracts on the project, held a 100% stake in the venture.

The chief executive of SNOC, Hatem al-Mosa, said: “After the Mahani discovery and also with our exploration program with Eni, in addition to some other external factors, we have decided to put the LNG project on hold until we have a better understanding of the size of the Mahani discovery and the prospect of having additional discoveries within Sharjah.”

He said the coronavirus pandemic and associated drop in oil and gas prices was unlikely to affect Mahani’s development because gas from the field is destined for the local market. “The gas is all dedicated to the market 100% and already committed and demand is there ... We don’t actually see much of an impact on gas production in Sharjah as result of demand reduction in the world”, he added.

Jebel Ali

Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) announced in February that it had made the Jebel Ali gas discovery on the back of drilling ten exploration and appraisal wells in its first ever exploration programme in neighbouring Dubai. It is to be jointly developed by ADNOC and the Dubai Supply Authority (DUSUP), Dubai’s state gas supply company. Most of the UAE’s oil and gas production is located in Abu Dhabi. Dubai’s economic boom has been fuelled by national and regional oil and gas income, but its own oil production peaked in 1991 at 410,000 b/d and has been declining since.

ADNOC says that it will develop the field, which covers 5,000 km2, using unconventional drilling techniques, including hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling. UAE Minister of State and ADNOC Group CEO Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber says that the company will now embark on more appraisal work to further determine the scope of the find.

Reserves on the new discovery are estimated at 80 trillion ft3, making it the biggest gas find made anywhere in the world since 2005, when the Galkynysh field was identified in Turkmenistan. If the reserves estimate is borne out, it would be the fourth biggest gas field ever discovered.

However, Palzor Shenga, an analyst at Rystad Energy, says that it is too early to confirm the size of the field, but added: “Even if this new discovery turns out to have only 8 trillion ft3 of recoverable resources — one-tenth of the preliminary official estimate — that would still be enough to enable the UAE to become energy independent by 2030, potentially removing its reliance on import volumes from neighbouring countries like Qatar...We also see a decline in domestic gas demand after 2030 that will further limit the need for imports.”

Jebel Ali’s description as ‘shallow’ suggests that development costs per unit of energy could be low providing there are no significant technical or geological problems. “The shallow nature of the discovery will also mean much lower development costs than some of Abu Dhabi’s sour gas resources”, said Liam Yates, research analyst, Middle East & North Africa upstream at Wood Mackenzie. Some sour gas fields in the country have not been developed since they were discovered in the 1980s. It was felt cheaper to rely on gas imports, particularly through the Dolphin pipeline from Qatar.

Some sources within the region suggest that first gas could be produced on Jebel Ali by 2025, with EPC contracts signed next year. The fact that ten wells have already been drilled means exploration work is already well advanced, but even so five years is an ambitious timeline for such a large field. Developers usually want to have a firmer idea of field size before embarking on development, although the UAE’s desire to end its reliance on Qatari gas imports may mean that it wants to sanction the first phase as quickly as possible.

The Covid-19 pandemic has badly affected oil and gas producers around the world, but the UAE is one of the best positioned to weather the crisis. Cushioned by ADNOC oil production of 3mn b/d and sovereign wealth funds, it should have the financial muscle to fund the first phase of Jebel Ali’s development.

Increased LNG export potential

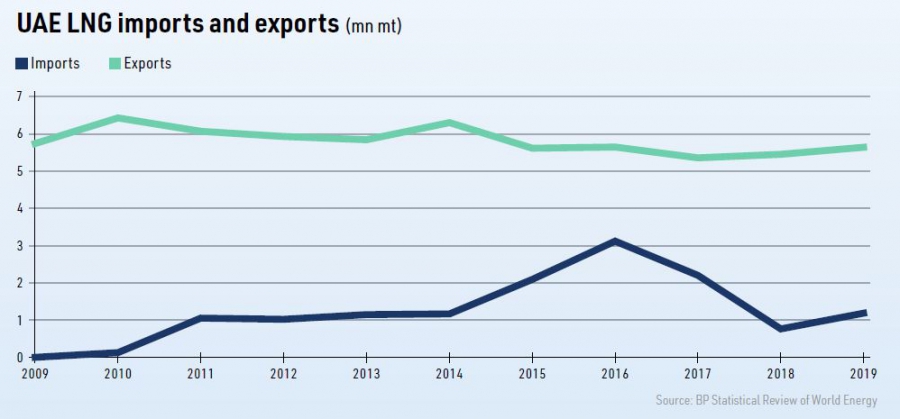

Aside from the impact on Sharjah’s planned FSRU, the development of Jebel Ali is likely to end the import of LNG elsewhere in the UAE. There have been FSRUs in Dubai and Abu Dhabi since 2014 and 2016 respectively, but the contract on Dubai’s unit, which has handling capacity of 1bn ft3/d, expires in 2025. UAE LNG imports peaked in 2016 at about 3mn mt, but had fallen to 1.2mn mt in 2019, while the country’s LNG exports have been running at about 5.7mn mt for the past five years.

Gas from Jebel Ali could also be used to boost production at the ADNOC LNG plant, which has production capacity of 6mn mt/yr. Most cargoes in recent years have been contracted to Japan’s Jera, but the majority of cargoes between now and early 2022 have been sold to BP and Total. ADNOC LNG is owned by ADNOC (70%), Mitsui (15%), BP (10%) and Total (5%).

The discovery could also enable the development of new LNG production capacity in the UAE. The country is fairly well placed to market any new LNG production in the world’s biggest LNG markets – Japan, South Korea and China. However, it will face stiff competition in the form of the planned step-increase in Qatari production, projects in the United States and planned LNG plants in Mozambique and possibly Tanzania.

Domestic threat to higher LNG exports

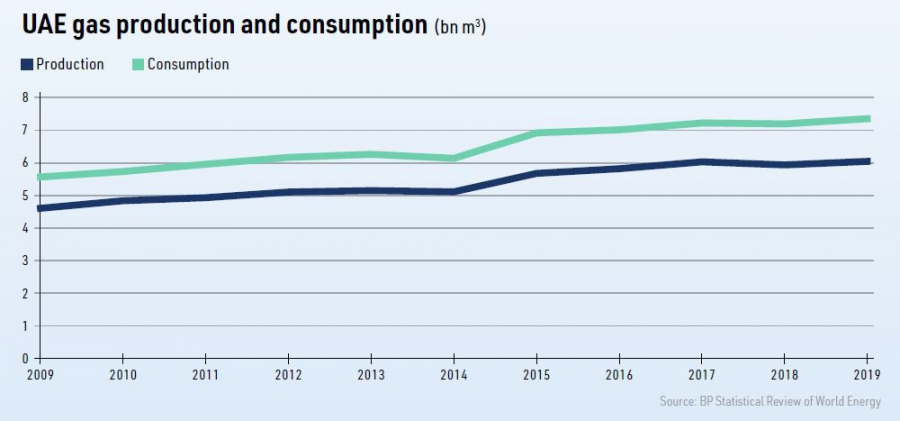

Jebel Ali’s ability to feed new LNG production trains relies in part on how quickly domestic gas consumption grows. The UAE produces about 6.2bn ft3/d of natural gas, but consumes 7.4bn ft3/d. It became a net gas importer in 2008 as domestic demand for power sector feedstock and gas for reinjection to support oil production increased sharply.

As a result, gas from the giant field will be supplied to DUSUP in the first instance “to support Dubai’s economic growth ambitions and enhance its energy security”.

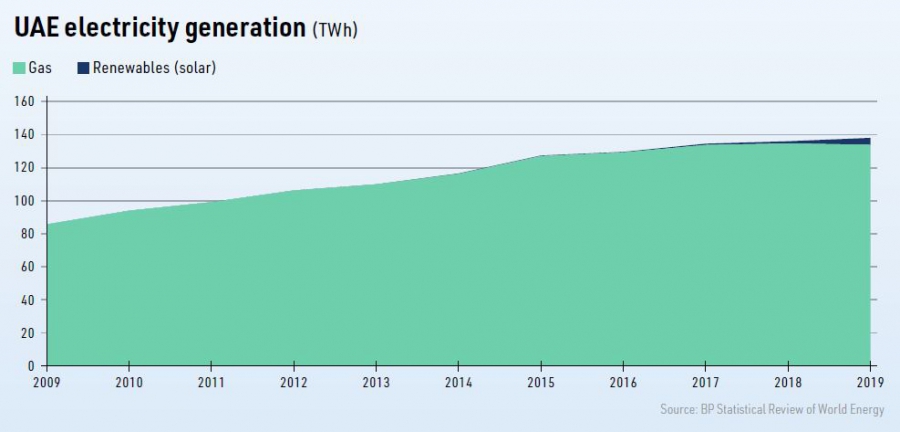

It will be interesting to see what impact the project has on Dubai’s generation mix. The city is currently heavily reliant on gas-fired capacity, but new solar, nuclear and coal-fired capacity is on course to reduce the role of gas. The UAE government has set a target of decreasing the proportion of gas in the generation mix from 76% in 2018 to 61% by 2030 and 38% by 2050, with 26% coming from renewables, 12% from coal and 6% nuclear by 2050.

Korea Electric Power Corporation (Kepco) is developing the 5.6 GW Barakah nuclear plant, where the second reactor was completed in mid-July, while the 5 GW Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park is the biggest project in the country’s renewable energy programme. However, the government predicts that power consumption will increase by an average of 1.4% over the next ten years, so it is possible that power sector gas consumption volumes may not fall at all between now and 2050.

The UAE government expects gas demand to peak this year and then start to decline, but Jebel Ali could be used to drive ADNOC’s planned increase in petrochemical production from 4.5mn mt/yr in 2016 to 11.4mn mt/yr by 2025 under its Strategy 2030. It aims to invest $45bn alongside foreign partners in petrochemicals and refining at the Ruwais hub between now and 2025, absorbing more gas that could otherwise be made available for LNG production.

The petrochemical plans are part of ADNOC’s wider strategy to reduce its reliance on upstream operations. All these projects could influence how quickly new LNG production capacity is developed in the country.

UAE gas reserves and production are increasing even without the sizeable addition of Jebel Ali. Abu Dhabi’s gas reserves now stand at 273 trillion ft3 of conventional gas and 160 trillion ft3 of unconventional gas reserves after the Abu Dhabi Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC) increased its reserves’ estimates late last year. The SPC calculates that the country now has the world’s sixth biggest gas reserves, which should be more than sufficient to achieve the UAE government’s aim of becoming self-sufficient in natural gas production and possibly even ramp up its LNG exports.

In November 2018, the SPC set a target of ensuring $132bn in investment in ADNOC oil and gas projects over the period 2019-23, partly in order to turn the country into a net gas exporter. S&P Global Platts estimates that the UAE will increase its domestic gas production by about 1.4bn ft3/d by 2024 on the back of a string of discoveries, many of them ultra-sour offshore finds, which have been made over the past few years.

ADNOC, Eni and Germany's Wintershall are already developing the Ghasha gas project, which is expected to yield 1.5bn ft3/d by 2025. In addition, the Abu Dhabi state oil company is working with Occidental Petroleum to increase output on the Shah gas field by 200mn ft3/d to 1.5bn ft3/d.

However, the discovery of Jebel Ali seems to be affecting ADNOC’s enthusiasm for developing other fields. In February, it awarded EPC contracts to the UK’s Petrofac on the Dalma gas project, which is part of the wider Ghasha development, but these were cancelled in April. Ghasha is an ultra-sour gas field and ADNOC is likely to deprioritise higher cost developments in favour of Jebel Ali.

Implications for Qatar

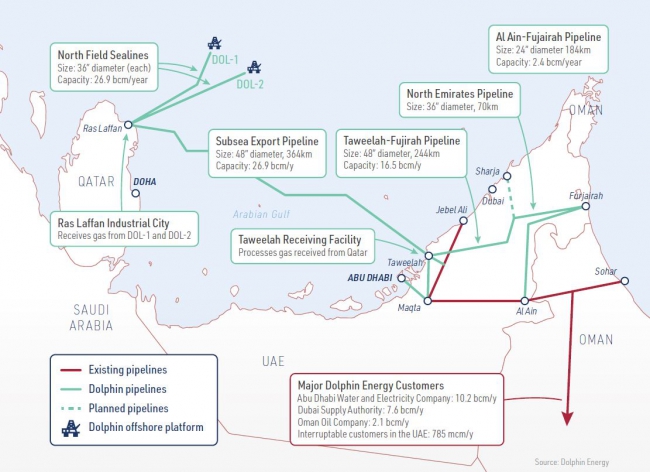

A combination of the completion of alternative sources of power generation and the development of the Jebel Ali gas field could see the UAE halt gas imports entirely. Various UAE emirates import gas from Qatar’s North Field either as LNG or via the Dolphin pipeline, which was completed in 2006. Dubai alone imports up to 2bn ft3/d under contracts that run until 2032. Ending this trade would free up more Qatari gas for export in the form of LNG.

It is possible that Qatar and the UAE could negotiate a more rapid conclusion of the various gas supply contracts, although the Dolphin pipeline would probably remain in use as it is also used to supply Oman. Although Dubai and Abu Dhabi may be keen to promote gas self-sufficiency, the situation is complicated by the 51% stake an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, Mubadala Investment Company, holds in Dolphin Energy, with the remaining equity owned by Occidental Petroleum Corporation and France’s Total (both 24.5%).

Relations between the UAE and Qatar have been tense since 2017 when the former joined Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt in imposing sanctions on Doha. They accused it of supporting Islamic State, Al Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood. They also opposed Doha’s efforts to improve relations between Iran and the Gulf states, and the ability of Qatari state-funded broadcaster Al Jazeera to criticise governments across the region.

The government of Qatar, which refutes allegations it has supported terrorist groups, describes the sanctions as a blockade and has been forced to diversify its economy because of its former reliance on Saudi Arabia and the UAE in particular. Its economy is based on its huge gas reserves and its position as the world’s biggest LNG exporter. On 14 July, the international Court of Justice ruled that attempts to restrict air access to Qatar were illegal.

The long-running dispute could encourage the UAE to ensure that gas production from Jebel Ali does displace Qatari imports before embarking on higher LNG exports itself, rather than assuming that the neighbouring state could act as a fallback option should it take longer or prove more expensive to develop the new discovery than predicted.

It is possible that ADNOC is playing up the size of the Jebel Ali reserves in order to put pressure on Qatar and encourage Dubai to end its reliance on the Dolphin pipeline. However, Doha is unlikely to be inclined to relieve the UAE of its contractual obligations to continue importing Qatari gas until 2032.