Australia revives reserve plan [NGW Magazine]

As 2019 drew to a close the Australian government had a surprise in store for the country’s natural gas exporters. On December 5, while praising the government’s efforts to shore up domestic gas supplies, Australia’s natural resources minister Matthew Canavan quietly announced that the government would be working with local authorities to “implement a National Gas Reservation Scheme”.

The minister’s statement raised eyebrows for two reasons. First, it came more than a year ahead of a previously announced deadline and, second, it ran counter to recommendations made by the Productivity Commission to the Senate just two weeks earlier.

Supply security

Canavan and energy minister Angus Taylor released a joint statement on August 6, 2019 saying they would consider a gas reserve policy as part of an effort to “help secure gas supplies, put downward pressure on prices and encourage new investment in gas supplies.”

At the time, the ministers said the government’s efforts, including the introduction of Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism (ADGSM) in 2017, had helped to reduce east coast gas prices by up to 50%. The ADGSM empowers the government to restrict gas exports from projects that run at a deficit to the local market, though these powers have never been used.

Canavan and Taylor said they would bring forward the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science’s (DIIS) review of the ADGSM from 2020 to 2019, consider possible national gas reservation scheme options with a decision to be made by February 2021 and also increase gas market transparency and supply by continuing reforms through the COAG Energy Council.

However, on December 6, 2019, Canavan said the government would continue working to keep downward pressure on east coast gas prices including through the introduction of a gas reserve policy scheme.

“We recognise that many businesses are still doing it tough with energy prices and I am focused on keeping gas prices down so we have a vibrant manufacturing and processing sector in rural and regional areas,” he said. “Western Australia has shown that a successful LNG export industry can survive and thrive with a gas reservation policy. I will ensure that gas is available and affordable for industry on the east coast as well, and will work with states and the Northern Territory and industry to implement a National Gas Reservation Scheme.”

The announcement followed a statement highlighting production gains on the coasts and did not provide additional information on how the minister expects the scheme to function beyond the reference to WA. It would be safe to assume, however, the state will serve as a model for the central government. WA has reserved 15% of all its gas production for the local market for years and yet continues to attract billions of dollars in gas project investment.

Indeed, Rystad Energy has forecast that the state’s Perth Basin will reach a peak production of 400mn ft3/day by 2024. The consultancy said on December 17, 2019 that the basin was expected to surpass the mature Cooper Basin in South Australia and – given an anticipated uptick in west coast prices – would “begin its rise to national if not international significance.”

Back on the east coast, the federal government is hoping that it can also create a climate that is attractive for upstream gas investors while still mollifying industrial and residential gas users by ring-fencing production. A government commission, however, has expressed scepticism that WA’s system can be successfully implemented at a national level.

Seed of doubt

In November 2019, the independent Productivity Commission submitted its report on Australia’s oil and gas reserves to the Senate Economics References Committee. The commission said that while a gas reserve scheme would divert gas from the export market to domestic users, forcing down prices in the process, it “would distort resource allocation, with economic losses compounding over time.”

It said investors would up their commitments to gas-intensives industries based on the fact that feedstock costs were below prices set in a free market. This is exactly the outcome these industries have called for, however.

Chemistry Australia, for example, released a report in August 2019 arguing that not only did the petrochemical sector contribute A$38bn (US$26.26bn) to Australian GDP but that it also added significantly more value to the gas used than the LNG industry. According to Chemistry Australia’s calculations, the petrochemical sector added A$286mn of value to every petajoule of gas it used – 33 times higher than LNG exporters.

The commission, meanwhile, said no domestic reserve policy could prevent local gas prices from rising in the long term. “By reducing the return on new supply sources, the reservation would decrease incentives to invest in gas exploration and development. The gap created between domestic prices in the eastern market and export prices likely under such a policy would especially weaken incentives to invest in projects that would produce solely for the eastern market, given that all of a domestic project’s production would be sold at prices below the market level,” it warned.

The government remains unconvinced, as evidenced by Canavan’s announcement in the weeks that followed. The government is walking a thin line balancing the interests of natural gas exporters and local consumers and sees the WA scheme as a solution that will work for the rest of the country.

While the industry will look to the government over the course of the year to reveal more of its plans surrounding the gas reserve scheme, investors may also want to keep an eye on policy decisions by the Victorian State government in the first half of 2020.

Decisions and repercussions

When Canavan and Taylor first flagged up the possibility of a natural gas reserve policy, they exhorted local governments to work with them to remove restrictions on gas exploration.

A wave of unconventional and onshore drilling moratoria swept across the country a few years ago in response to mounting pressure from both environmentalists and the farming sector.

Now Victoria stands alone as the only state, with meaningful onshore exploration potential, that still maintains a blanket ban on both unconventional and onshore exploration.

In his December 6 statement, Canavan took the opportunity to rail against Melbourne’s Labor government for its stance on the upstream sector. He said: “The [Dan] Andrews government seems intent on shutting down industries, from vegetable processors to aluminium smelters operating in regional areas of Victoria while they pander to green activists and Greens in inner city Melbourne.”

Victoria’s ban on conventional onshore exploration is due to expire on July1, 2020 and the state government will undoubtedly be trying to figure out a response that does not leave it open to a coalition attack. Victoria needs gas and lifting the ban on conventional onshore exploration makes sense, given that production from the prolific Bass Strait is winding down. However, the state government will be eager not to hand an easy political win to its rivals in the federal government.

Canavan has drawn a line in the sand and regardless of whether the Andrews government steps over it or not, Canberra is surely prepared to paint it as another victory for central government energy policy.

|

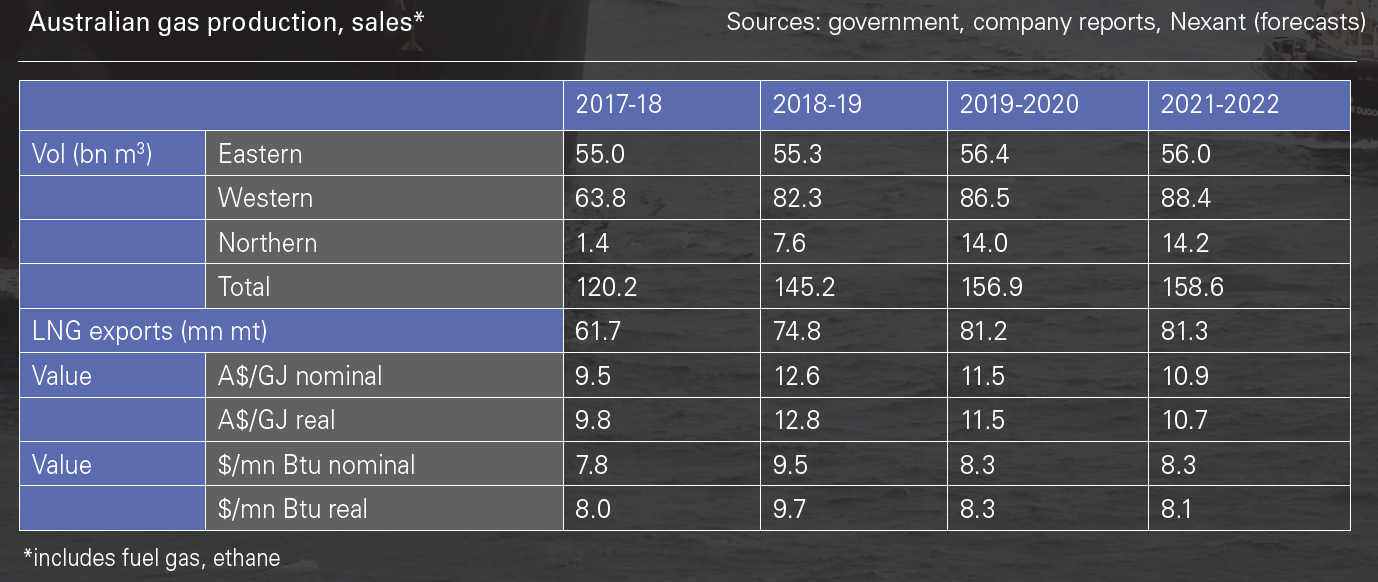

Value drains from LNG Exports of Australian LNG have lost some of their shine over the last few years, as the gap widens between spot and long-term contracts that are based on crude oil prices. While the drop in oil prices narrows the gap and will help buyers, it is still very large and sellers are seeing their expensive investments take longer to pay back. A government report, Resources and Energy Quarterly published in late December, says the “indicative” oil-linked contract price for Australian LNG in Q4 2019 was estimated to be around US$10.50/mn Btu (A$16.29/GJ), down slightly from $10.60/mn Btu in the September quarter. It notes: “There are potential implications for long-term contracts if this gap persists for a sustained period of time. Buyers are reportedly reducing purchases on long-term contracts – and increasing purchases of spot cargoes – where their contractual flexibility permits, and pushing to have contract prices lowered during the periodic price reviews that are built into long-term supply agreements. The report warns that the value of the country's LNG exports will decline from A$50 ($34)bn in 2018–19 to A$49bn in 2019–20, and fall back further to A$47bn in 2020–21, driven by declining oil-linked contract prices and an appreciating exchange rate. This is despite output rising from 75mn metric tons in 2018–19 to 81mn mt in 2019–20, as the last two projects in Australia’s recent wave of LNG investment, Prelude and Ichthys, ramp up. The new forecasts have been revised down from the September 2019 Resources and Energy Quarterly, by A$2.7bn and A$2.2bn in 2019–20 and 2020–21, respectively. In 2019–20, growth in export volumes is expected to partially offset the impact of lower oil-linked contract prices, as the Prelude and Ichthys projects continue to ramp up production. Production at Ichthys has ramped up ahead of schedule, reaching around 95% of nameplate capacity during the September 2019 quarter, up from around 80% in the June quarter. Partially offsetting export growth from new projects, maintenance works at Train 1 at Gorgon LNG is expected to reduce export volumes in the December 2019 quarter. And tapering production at Darwin LNG – as gas from the Bayu-Undan field is exhausted – is expected to see a reduction in export volumes towards the end of the outlook period. The report also comments on the effect of the US-China trade talks, following the mid-December agreement: "LNG trade flows will likely continue to be influenced by any resolution or escalation of US-China trade tensions.… If LNG continues to be caught up in trade tensions, this may discourage or delay final investment decisions for a second wave of US LNG projects." The report says Australia has accounted for the majority of the increase in China’s imports since September 2018 but adds that “it is difficult to attribute this increase directly to the effect of tariffs, given China’s rapidly growing LNG demand and the ramp up of new Australian projects over the same period.” On current estimates, Australia is expected to marginally edge past Qatar as the world’s largest LNG exporter in 2019, shipping an estimated 78mn mt of LNG compared with an estimated 75mn mt from Qatar. The title is not certain however, with a lack of clarity around the precise level of Qatar’s LNG exports, the report says. The CEO of upstream lobby group Australian Petroleum Production & Exploration Association Andrew McConville said the data highlighted the significance of LNG exports for sustaining Australia’s economic growth, maintaining living standards and lowering global carbon emissions. “Australia’s LNG projects will deliver decades of economic growth, jobs and exports,” he said. “The billions of dollars invested in these projects have also benefited the growing domestic market. The LNG industry is and will remain a very large supplier of domestic gas to the east coast gas market." William Powell

|