Analysis | Can Central Asian gas exporters rely on China?

Central Asia’s natural gas producers have only one eager buyer: China. And though China has a growing appetite, it has signaled intentions to source more energy domestically. What does this mean for Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan?

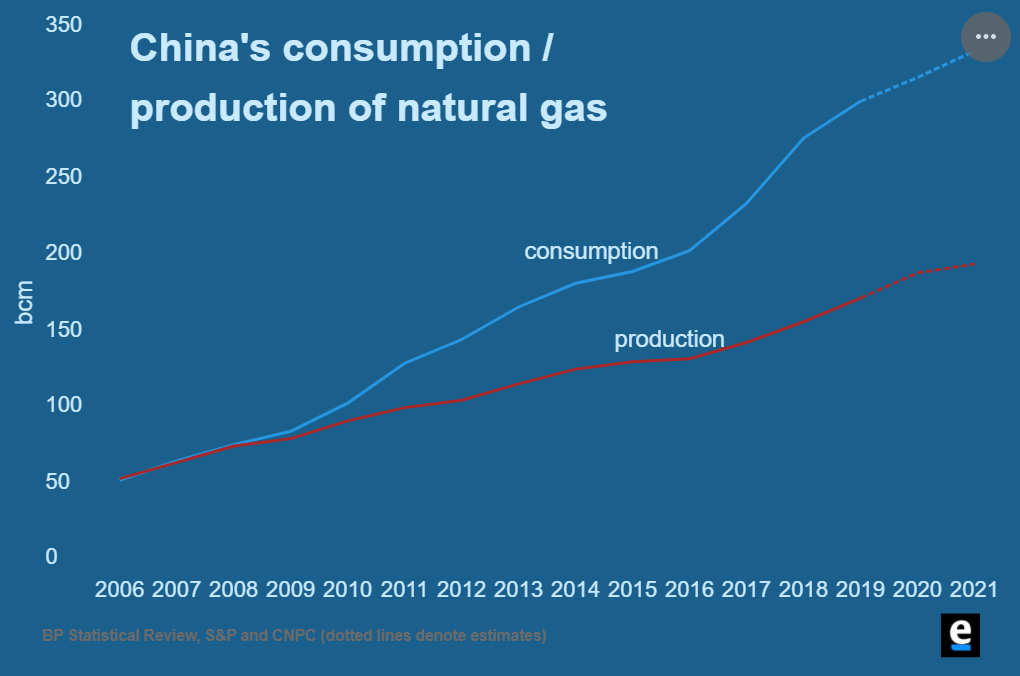

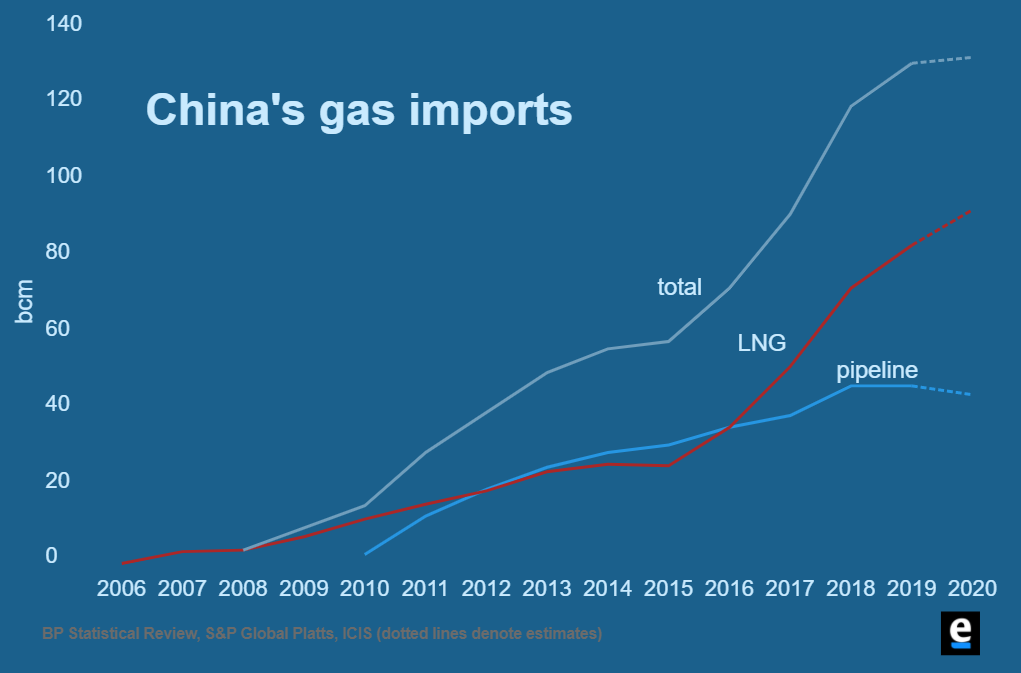

A little over a decade ago, China produced enough gas to meet its own demands. These days, it imports about 42 percent of its needs. Central Asia supplies about a third of China’s total gas imports and 15 percent of demand. The rest travels through pipelines from Myanmar (3 percent of total imports) and Russia (3 percent of imports and rising) – or by sea as liquified natural gas, which accounts for over two-thirds of imports. (China will soon be the world’s largest LNG importer.)

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

China’s demand for gas will double by 2035, so Central Asian producers will remain part of their neighbor’s import portfolio. Yet Beijing’s hopes to curb reliance on imports while cutting emissions in the long-term raise questions about the need for additional pipelines from Central Asia, such as Line D, a planned extension to the existing network.

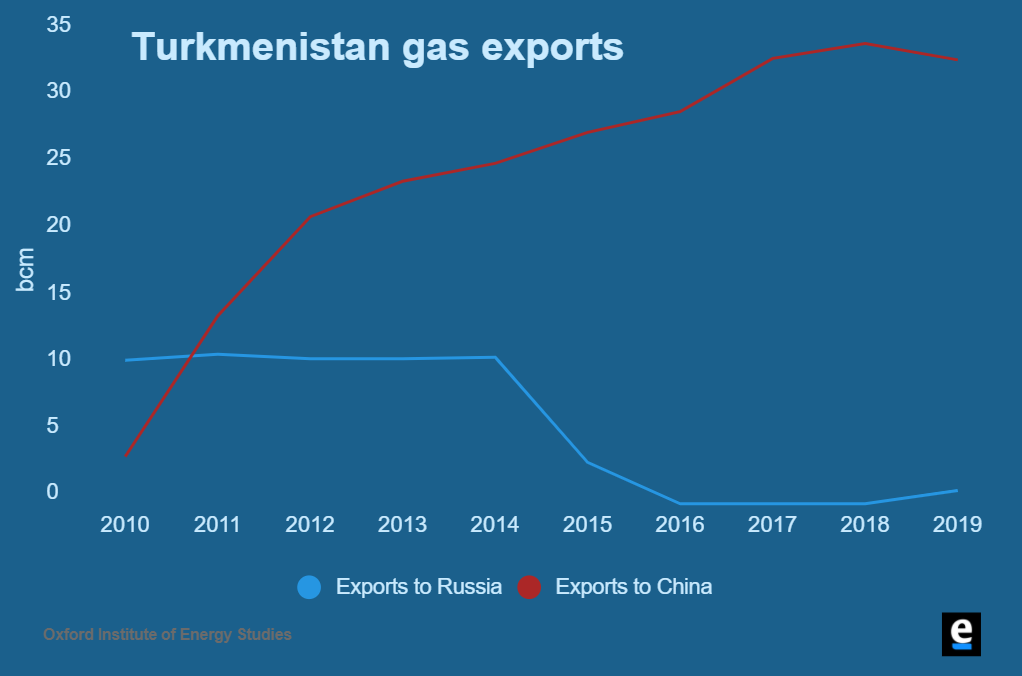

China imported a combined 43 billion cubic meters (bcm) from Central Asia in 2019, according to estimates from the BP Statistical Review. Back in 2010, that figure was just 3.4 bcm. Turkmenistan, Central Asia’s largest gas exporter, became especially dependent on China when its exports to Russia slid to zero in 2016. In mid-2019, Russia agreed to resume importing 5.5 bcm per year of gas from Turkmenistan, a fraction of what goes to China.

While China is importing more LNG, it is contractually obliged to pay for a certain amount of gas from Central Asia. Such a “take-or-pay” provision is included in most long-term gas contracts. “These volumes could potentially be reduced, but they are unlikely to fall below 70 percent of today’s quantities,” says Sergei Kapitonov of the SKOLKOVO Energy Center in Moscow.

“Any gas contract includes mechanisms for renegotiation,” Kapitonov notes. “China will definitely use its right to renegotiate if they see that the market can provide cheaper or more flexible gas from other producers. In this regard, gas exports from Central Asia are much more vulnerable than gas exports from other producers because at the moment Central Asia has no viable export alternative to China.”

The burden of monopsony came into the spotlight last March, when China declared force majeure due to the pandemic and cut Central Asian gas imports.

A prolonged drop in gas sales would be calamitous for Turkmenistan, where they account for over 80 percent of export revenues. Uzbekistan, which exports gold and cotton as well, is better placed to handle shifts in China’s energy appetite. Tashkent also says it hopes to phase out gas exports by the mid-2020s to help mitigate domestic shortages. In any case, these countries have struggled to find alternative buyers for decades.

For now, their gas exports should be secure because they are reliable. Asian spot LNG prices have faced extreme volatility in the past year, falling to record lows in 2020 and then surging in early 2021 with winter heating demand, leading China to bring in more from Central Asia.

LNG also arrives at coastal terminals, entailing geopolitical risks. “The U.S. trade war reminds China of the risk of importing energy, especially on ships,” says Stephen O’Sullivan at the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies. “Having a pipeline with Central Asia makes [China] feel more comfortable. Pipeline gas is clearly seen as more secure.”

In the long-term, Beijing’s push for greater supply security is a threat to gas exporters hoping to capitalize on China’s surging demand.

The National People’s Congress recently addressed supply security in its 14th five-year plan, released on March 11, by introducing minimum levels for domestic energy production. Beijing also opened up the sector to foreign firms last year, allowing them to explore and produce. Foreign gas producers that sell to China could lose out.

The five-year plan also aims to increase the share of non-fossil fuels (including nuclear and hydropower) in the country’s energy mix to “around 20 percent” by 2025. The pivot to alternatives will still leave room for natural gas, given that it is seen as a “bridge fuel” to help move away from coal; China has pledged to become carbon neutral by 2060, which will ultimately lessen the use of coal and crude oil faster than cleaner-burning natural gas.

With China’s gas imports expected to stay flat through 2025, the big question for neighbors is whether China will need another pipeline – and which one. Line D was agreed upon in 2013 but has been slow to advance – suggesting that China may be losing interest. Line D, which would boost China’s purchases by up to 30 bcm per year, would rival the proposed Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, which would bring 50 bcm per year from Russia to eastern China. China will likely only need one of these.

Originally published by eurasianet.org

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.