Africa’s near-term LNG potential [Gas in Transition]

Africa has a raft of new, large-scale LNG projects in the pipeline, but it can respond to the global energy crunch in the nearer term, by increasing the use of terminals that are already in operation, and deploying smaller-scale floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs).

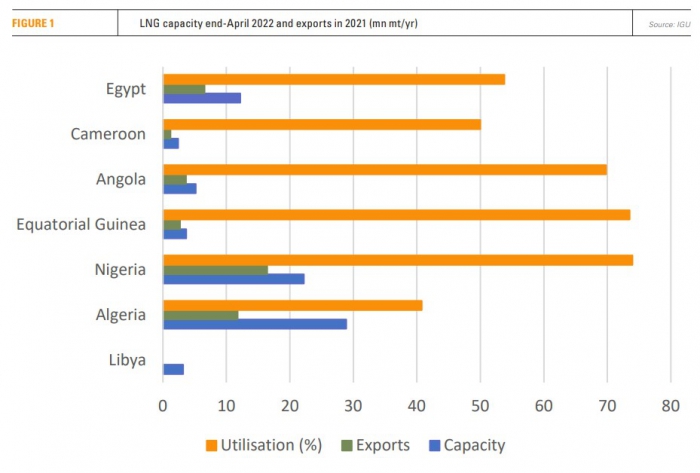

The continent has close to 78mn metric tons/year of liquefaction capacity, but only 54% was utilised last year, primarily as a result of constraints with upstream supply. But high prices, and in some cases policy improvements, are helping to spur the development of new fields.

Algeria

Algeria exported 11.8mn mt of LNG in 2021, despite being capable of delivering 29mn mt/yr. Even though its production increased by 25% that year to 101bn m3, most of the surplus was funnelled into pipelines to Europe.

The country is expected to continue prioritising increased pipeline exports, considering high demand in Europe and the comparatively low transport costs compared with LNG shipping. The country has three pipelines to the continent - the 32bn m3/yr TransMed, the 10.7bn m3/yr Medgaz and 12bn m3/yr Maghreb-Europe lines, although the latter was taken offline in November last year, due to fallout from Algeria and Morocco’s long-standing territorial dispute.

Combined, the pipelines delivered 34.1bn m3 of gas last year, meaning that even if Maghreb-Europe is taken out of the picture, there is more than 9bn m3/yr of capacity still available.

Italy’s Eni and Algeria’s Sonatrach agreed in April to bolster pipeline gas supplies to Europe, and this deal is expected to utilise nearly all remaining spare capacity at TransMed. Additional LNG supply will depend on whether production growth outpaces the rise in pipeline deliveries.

Algeria is struggling with production decline at older fields, while also coping with rising domestic demand. The giant Hassi R’Mel field currently accounts for half of supply, but it is past its peak and is due enter end-of-life decline from around 2025.

On the other hand, improvements in Algeria’s investment climate following the ousting of former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika in 2019, coupled with high oil and gas prices, are spurring new field activity that is yielding clear results. Sonatrach discovered a new reservoir at Hassi R’Mel in June that alone will provide an extra 3.65bn m3/yr of gas. With no shortage of customers, this should bolster LNG exports and not just pipeline sales, with Algeria’s energy minister predicting in June that liquefaction would reach 22bn m3/yr this year.

Nigeria

Over in Nigeria, NLNG’s liquefaction trains shipped out 16.4mn mt of LNG in 2021, compared with a total capacity of 22.2mn mt. A seventh train is now 30% complete, and should come online by 2025, raising national capacity to 30.8mn mt. But upstream issues have limited gas supply availability – namely outages along the pipelines that feed the LNG complex, often due to sabotage. This is a persistent problem that is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon.

Egypt

Egypt has 12.2mn mt/yr of LNG capacity, but delivered only 6.6mn mt last year. But output is set to grow as more new discoveries are put into production and the country receives increasing supply from Israel. The country’s gas production soared to 67.8bn m3 in 2021, from 58.5bn m3 in the previous year.

It should be noted that some new supply will be directed to the growing domestic energy market. In the short term, though, government efforts to conserve energy supply could free up some 16mn m3/d of extra gas for export, according to Rystad Energy.

Libya

As for Libya, its sole 3.2mn mt/yr Marsa El Brega LNG plant has been inactive since 2011, amid continued instability and conflict, and there seems little prospect of this changing. All spare gas supply available is much more likely to be funnelled to Italy via the Green Stream pipeline, which has a capacity of 11bn m3/yr.

East Africa

The prospects for LNG from Sub-Saharan Africa vary greatly in terms of timing and scale. Plans for two onshore LNG facilities in Mozambique are currently on hold because of the security situation in the country’s gas-rich north. The TotalEnergies-led 12.9mn mt/yr Mozambique LNG project was put on hold in March, and the government has indicated it does not expect a decision on its resumption until next year. Meanwhile, ExxonMobil is yet to take a final investment decision on its Rovuma LNG plant, and says it does not envisage such a step anytime soon.

Offshore, however, Mozambique is awaiting the launch by year-end of Eni’s 3.4mn mt/yr Coral Sur FLNG. Delays at the onshore projects could result in developers shifting their plans offshore, where their investments are better protected from security concerns on land.

Tanzania continues to tout the potential of its first LNG project, and while the new government has signalled it will provide better terms to developers Equinor and Shell, a host government agreement is not yet in place. A final investment decision is being targeted for 2025.

West Africa

BP and Eni’s decision to merge their Angolan businesses into the Azule Energy joint venture should be good news for the 5.2mn mt/yr Angola LNG plant, which operated last year at 70% of capacity. The pair took an FID in July on the development of Angola’s first non-associated gas project, Quiliuma and Maboqueiro, providing additional supply for Angola LNG from 2026.

In Mauritania and Senegal, BP’s Greater Tortue Ahmeyim LNG project is nearing completion and is anticipated online this year. Its first phase is small, providing only 2.5mn mt/yr, but its capacity will be expanded to 10mn mt/yr at a later stage. BP had wanted to ramp up capacity faster, but slowed the project down in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, the Hilli Episeyo FLNG off Cameroon is currently working at only half of its 2.4mn mt/yr capacity, but utilisation should increase by 200,000 mt this year and a further 400,000 mt in 2023. Eni’s 3mn mt/yr FLNG off Congo-Brazzaville should start up in 2023, and the company signed a heads of agreement in February to deploy one of New Fortress Energy’s “Fast LNG” plants in the country.

In summary, while there are a number of large-scale LNG projects at various stages of development in Africa, it would seem that increased utilisation of existing plants, and the use of FLNG, will have a more meaningful impact on the continent’s liquefaction capacity in the next couple of years.