A Strategy Called the Russian Roulette

Everybody knows about this game. In principle it has no connection with natural gas. Though, when looking at the current situation for Russia, and when drawing it on a map (see below), one can wonder if Russia is not actually playing this game. Worse than this, it seems that she is playing a “reversed roulette” where the revolver is actually filled with bullets and only one hole remains empty. As a matter of fact, Russia finds itself in an uncomfortable situation that can lead us to wonder if its strategy is simply… to wait (or hope) that all options and scenarios concerning natural gas supplies that are “embarrassing” for her fail. Here comes the explanation.

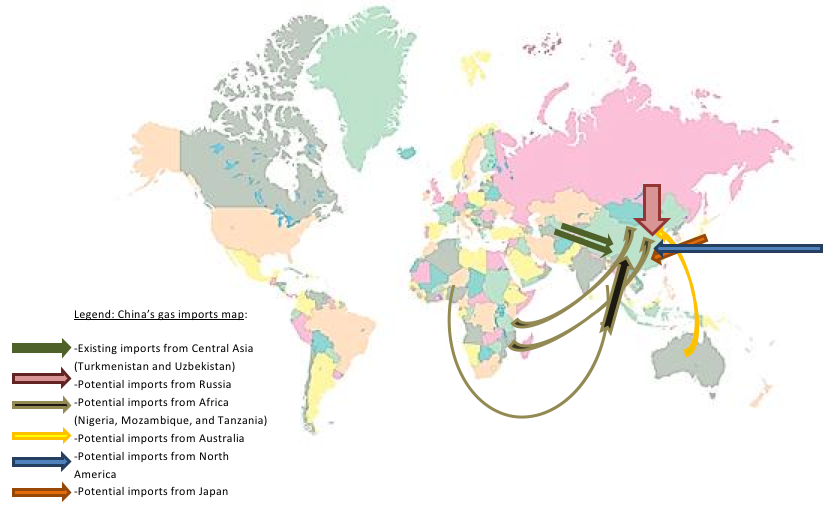

As far as natural gas is concerned Russia is challenged on every side. On the “European front”, the challenge is mainly coming from Brussels’ political will. This latter wants to assert its normative power by imposing its rules on its Russian neighbour (how pertinent is this European stance is another topic…). In the meantime, there is the will to get rid of Russian gas. A good illustration of this last point is the Med-Gas-Ring mega-project that the European Commission had in mind not so long ago and may still have in mind. This ambitious project was to create a gas ring around the Mediterranean Sea by connecting existing gas pipelines. How actually feasible it would be is another question, what matters here is that it emphases the seriousness of the will to get rid of Russian gas. On the “Central Asian front”, Russia is being challenged by Chinese energy diplomacy. And on the “Asian front”, Russia’s privileged position as a supplier there is being challenged by a rather wide panel of supply options for China.

On the “European front”, the challenge is mainly coming from a political will (not shared by all though) to send Russia back in its boundaries. Mega-Project such as the Mediterranean Gas Ring and ambitious climate targets (80%-95% of renewables by 2050) that have actually a geopolitical taste make clear that Brussels is rather cold when it comes to welcoming Russian gas in Europe. The problem for Russia is that the European gas market is its biggest and most profitable export market; while other export options are still “shaky”. Indeed, Russian exports of liquefied natural gas to the North American market seem to be over now; and export prospects to Asia (China in particular) are still not fixed. This means that the European option, for Russia, remains the only viable one at the moment. The recent opening of the first and then of the second leg of the Nord-Stream pipeline could appear as a victory for Russia. But even this has to be questioned. First of all, the first thread is not yet fully-functioning. And second of all, while on the one hand Russians are fighting hard to promote long-term contracts and oil-indexed prices, on the other hand the supplies of gas from Nord-Stream to Germany allowed “this later to acquire an important, and profitable, gas distribution hub of its own, and Gazprom’s European partners can now sell Russian gas at the spot market. Poland is already buying it from Germany at a discount against Russian oil-indexed prices, and the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine are negotiating cheaper deals as well[1]. So the picture is not all pink in Russia’s traditional export market.

Looking at the “Central Asian” front now, the picture is also far from being all pink. Indeed, China has been rather effective in securing natural gas supplies from Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. In doing so, it has both challenged Russia in its traditional zone of privilege and weakened her in its bargaining position for exporting its gas to China. If one looks at the half-full glass, the evacuation of Central Asian gas resources toward East is a good news in that this Central Asian gas is then not flowing to Europe and therefore does not compete with Russian gas supplies there. An excess of optimism (or an excess of blindness) might even push us to think that these Central Asian exports are paving a golden way for Russian gas to flow to China in making this latter more and more dependent on gas, with the dreamed-end story for Russia of finding herself in the position to impose its conditions on China. What seems to be really happening is rather different. Indeed, Turkmen and Uzbek gas may not pave the way for Russian gas to flow to China. It would be the case if the panel of options for Chinese natural gas imports was limited. But it seems that is not the case. China quietly kept and is still keeping Russia on the hook while looking for further options for its energy security. And it seems to be working rather well. Chinese options for importing natural gas, in addition to Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, are Mozambique, Tanzania, Nigeria, Australia, USA, and even Japan if nuclear plants are back to operation[2]. In addition to this, the internal unconventional resources of China are to be put on the supply options map. Worse, more competitors in gas exports may mean lower price. This may finally mean for Russia not only less export to China but at an even lower price. All this is good for China. One could then wonder how Russia can seriously expect to impose its pricing condition on China. It is worth to ask ourselves if, behind the solid Russian stance toward China, we are actually witnessing internal “fights” in Russia between those oligarchs dreaming of selling at a high price and those (if any) more aware of the situation. One could also wonder when these “dreamers” will wake up…

The picture is a bit dark for Russia, but the story does not end here. What may look like a marvellous supply story for China and a nightmare for Russia has to be questioned. As far as North American liquefied natural gas exports are concerned, the United States are facing the dilemma of either supporting national economy by limiting exports so that power is affordable or to allow big companies to export. Prospects for shale gas exports from Canada are limited: high upstream costs and “plenty of competition’ on the market can make the building of LNG terminals economically unattractive. Furthermore, Australian LNG exports are being challenged by those potential exports from the US and also by Chinese unconventional gas production. In addition to this, Eastern African natural gas discoveries (Mozambique and Tanzania) may be good news but serious work has to be done there. The lack of infrastructures and facilities has to be addressed; trained workforce is much needed; opacity and corruption is also problematic. Unconventional gas developments in China are also questioned with issues such as water scarcity and geology. The building of new import terminals (fifteen planned at the moment) may not go alongside the development of unconventional gas, making the former risky. Potential pipelines from Russia and also Kazakhstan are also part of the supply options from China, and they could make LNG imports less attractive.

So finally, with so many uncertainties, is Russia’s bet on the failure of other options and scenarios that risky? The bet might be as risky as a playing a reversed roulette, but the winner takes it all.

Article and map: Yasmina Sahraoui

[1] Mikhail Khutikin, “Is Gazprom A Cannibal?”, 17.10.2012- RusEnergy

[2] The Japanese government adopted a resolution to phase out all nuclear power by 2040, but then toned it down and failed to make it official policy.