A Green Deal for Europe [NGW Magazine]

An idea coined in the US is finding its way to Europe. As Ursula von der Leyen is preparing her way to the European Commission (EC) presidency from November 1, there is increasing talk in Brussels for the need for a European ‘Green Deal’.

It represents a unique opportunity for the EU to move away from fragmented policy-making in climate change to a comprehensive and consistent policy framework. This can promote decarbonisation while also taking advantage of the economic and industrial opportunities it offers.

Von der Leyen announced September 10 the new team of commissioners and their portfolios. She has appointed Frans Timmermans - from the Netherlands – as executive vice-president to co-ordinate the work on the European Green Deal.

He will also manage climate action policy, supported by the Directorate-General for Climate Action. The plan is that the European Parliament (EP) will give its approval by October, so that the new EC will become functional by November 1. Handing the responsibility for the Green Deal and climate action to Timmermans highlights the importance von der Leyen places on these issues.

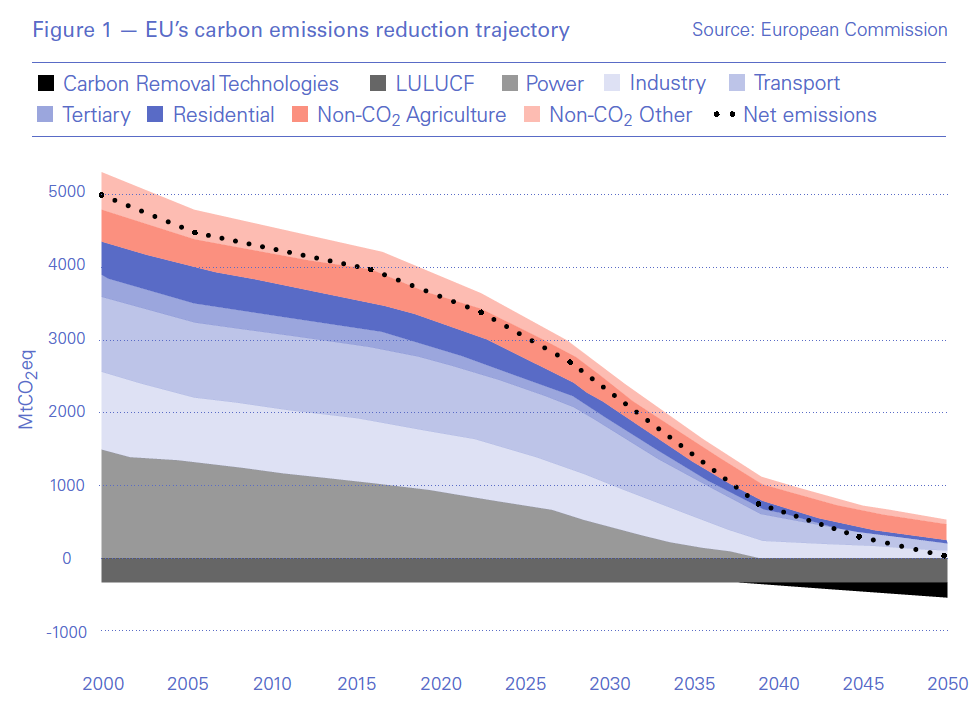

Green issues played a decisive role in von der Leyen being confirmed by the EP -- by a small margin -- president. She succeeded after pledging to strengthen EU climate action and to “reduce emissions by at least 50% by 2030” and possibly “increase the EU target for 2030 towards 55% in a responsible way.” This is in line with the target endorsed by the EP – in a non-binding vote in March -- to increase EU’s carbon emissions reduction target to 55% by 2030 below 1990 levels, from 40% now (Figure 1). She committed to present a ‘Green Deal’ for Europe during her first 100 days in office and to enshrine carbon-neutrality by 2050 into law, including:

Green issues played a decisive role in von der Leyen being confirmed by the EP -- by a small margin -- president. She succeeded after pledging to strengthen EU climate action and to “reduce emissions by at least 50% by 2030” and possibly “increase the EU target for 2030 towards 55% in a responsible way.” This is in line with the target endorsed by the EP – in a non-binding vote in March -- to increase EU’s carbon emissions reduction target to 55% by 2030 below 1990 levels, from 40% now (Figure 1). She committed to present a ‘Green Deal’ for Europe during her first 100 days in office and to enshrine carbon-neutrality by 2050 into law, including:

- Europe to lead the way in becoming the first climate-neutral continent;

- Investing in innovation and research;

- Extending the Emissions Trading System;

- Introducing a carbon border tax on imported goods to avoid carbon leakage;

Von der Leyen also undertook that the EU will lead international negotiations to increase the level of ambition of other major emitters by 2021. She said: "Our most pressing challenge is keeping our planet healthy."

She promised a just transition for all, “leaving nobody behind”, by putting together a Sustainable Europe Investment Plan that will support €1 trillion of investment over the next decade “in every corner of the EU.” But she also said: “Emissions must have a price that changes our behaviour…All of us and every sector will have to contribute.”

In effect the key policy priorities in the new ‘Green Deal’ are:

- a step-up in climate ambition, to set the EU in a new direction;

- innovation-driven competitiveness to help EU companies develop the required clean energy solutions;

- social justice to ensure an inclusive and affordable transition for all Europeans.

What the ‘Green Deal’ promises are comprehensive, inclusive, policies addressing climate, energy, environmental, industrial, economic and social issues required to achieve its objectives.

Clearly, with such pledges, climate issues will become mainstream in Brussels under von der Leyen. As Celine Charveriat, executive director of the Institute for European Environmental Policy, said: “She will be held personally accountable for delivering on her promises regarding climate action.”

The Greens parliamentary group will make sure of that. They did not support her candidacy as they thought it lacked ambition and now they have teeth: they have 74 MPs, keen to influence EP affairs.

However, given the lack of consensus among member states, von der Leyen may be facing an uphill battle to deliver on her climate change pledges. Acknowledging this, she said, cautiously: “If we want to make it to these ambitious goals we have to take every member state and we have to take the people and the economy with us.”

Words or action?

Given the huge implications of her pledges on EU’s energy future, energy security, climate change and the economy, the question is: can she deliver? Not only she has to satisfy the EP, but also the European Council, where opposition from central and eastern European states in June prevented agreement on 2050 carbon-neutrality.

Poland opposed EU’s 2050 emission reduction plans in June because it first needs to know what the total cost of transition will be, the impact on its economy and the social cost and how these will be mitigated. Once these issues are addressed, Poland is prepared to review its position again in December, but its goal is economic continuation.

The social factor and security of energy supplies during transition are key. Poland made it clear that it will need help from Europe. Similar views are shared by other eastern European states, notably Hungary, the Czech Republic and Estonia. The good news is that Timmermans recognises that Europe needs “a new social contract.”

Creating a new climate transition fund to support less advanced economies may provide the answers. Von der Leyen said: "Not all regions have the same starting point but we all share the same destination… This is why I will propose a just transition fund to support those most affected. This is the European way: we are ambitious; we leave nobody behind."

However, according to the EC, in order to achieve these targets, including carbon-neutrality by 2050, the EU will need to find between €175bn and €290bn additional investments annually. It also requires regulators, the economy and the financial sector to pull in the same direction at the same time. Delivering the new ‘Green Deal’ will not be easy and it will be costly. In addition, it will require support by all EU member states. While northern Europeans increasingly see climate and the environment as one of the most important issues, it is very low in the list of priorities of southern and eastern Europeans.

Referring to this need for unity, von der Leyen said: "We must first rediscover our unity; if we are united on the inside nobody will divide us from the outside.” But this may require moving away from European Council unanimity in decision-making on climate and energy, which will not be easy.

If the ‘Green Deal’ and transition to carbon-neutrality succeed, they could provide the EC and member states with an opportunity to unite around a common goal, with the EU playing a leading role worldwide.

But this should be tempered by the knowledge that even though EU’s emissions in 2018 were reduced to 2014 levels, emissions in China, India and the US are still rising. EU’s annual share of global emissions is already low, less than 10%, and is expected to fall to about 5% by 2030.

In addition, the economic realities and practicalities of implementing the new ‘Green Deal’ may yet temper its adoption. There are also fears that if others do not follow Europe could harm itself competitively by being a first-mover on climate.

Germany to the rescue

At a meeting in the Hague August 22, Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte discussed the joint management of the climate. That was a pivotal meeting, with Merkel confirming that she would back a Dutch proposal to step up the EU's 2030 climate targets significantly.

Germany and the Netherlands agreed to work together on climate measures to reduce carbon emissions by 55% by 2030 and to support von der Leyen’s proposal to make the EU climate-neutral by 2050.

This constitutes a major shift by Germany on climate issues. In September, the government will be presenting its measures to cut emissions drastically and put the country back on track for 2030. Merkel said that she “could very well support the Dutch proposal to reduce greenhouse gases in the EU by 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels.”

With Frans Timmermans in charge of implementing EU’s ‘Green Deal’, the new climate targets must be taken seriously. Moreover, co-ordinated action by Germany and the Netherlands could sway the European Council to approve carbon-neutrality by 2050. A target which already has the support of most EU states.

Implications for natural gas

Even though von der Leyen still has to devise specific and detailed policies on how the ‘Green Deal’ pledges on climate change will be implemented, clearly there will be major changes in EU’s energy sector, with implications on the future of natural gas in Europe.

Even though the EU may be on track to meet the current target to cut carbon emissions by 40% by 2030, achieving 55% is a much bigger challenge. It will require significant acceleration in the transition to a clean energy future in comparison to what has been considered to date.

A recent review showed that there is a long way to go to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. This will require a radical change across EU’s entire economy and implementation of more widespread decarbonisation strategies in all sectors.

But, worryingly, in a recent article on investments needed to achieve climate-neutrality, EC’s Michel Barnier did not make any reference to natural gas as being part of the solution. He talked about “investing massively in future mobility, energy-efficient buildings, and renewables, and in key technologies such as hydrogen batteries, new generations of solar panels, and green chemistry.” He also talked about applying strict CO2 emission limits to new passenger cars, public transport, and commercial sea and air transport, and “making Europe the first electric-vehicle continent by 2030.”

During the EU election campaign, Timmermans fronted a green agenda, promising to champion a sustainable Europe, with strong political commitment to addressing climate change and pledging to base the Commission’s work around the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement. With von der Leyen’s support and his new role, he will be in a position to follow up on these pledges.

Given Timmermans agenda, Barnier’s comments should be seen as a warning. The natural gas industry must make its case, compatible with the new ‘Green Deal’, if it is to be part of the new EC’s thinking.

In a climate-neutral Europe, all industries relying on burning fossil fuels will have to change or vanish beyond 2030. That will require full decarbonisation of natural gas sooner than later.

In a keynote speech to the Offshore Europe conference September 4, Total’s CEO Patrick Pouyanne said: “climate change is the single greatest challenge facing the industry, jeopardising its licence to operate, as well as its ability to attract new talent and fresh investment.”

He emphasised the need to bolster investment in new technology such as carbon capture and storage if the oil and gas industry is to cut its climate change impact. He added: “Our mission is to be able to provide reliable, affordable and clean energy to the world. All of these words are equally important, even if society is clearly putting emphasis on the last one of them: clean energy… All of our citizens around the world are really pushing us to act in ways to solve climate change.” He warned that the oil and gas industry must adapt or “go the way of the dinosaurs.”

Industry leaders at the conference also discussed the dual challenge of meeting climate change targets while delivering energy to the world’s growing populations, particularly in developing regions.

Until recently it was thought that gas has until 2030 to adjust to the new realities of climate change in order to retain its role in Europe’s energy mix well into the future. But the changes proposed in the new ‘Green Deal’ will bring this forward – change will need to start now, especially if the more ambitious target to cut emissions by 55% by 2030 in comparison to 1990 levels is to succeed.

|

Eurogas finds comfort The European utilities’ association Eurogas found comfort in the reference to gas contained in the letter from von der Leyen to the Energy Commissioner candidate, Kadri Simson. But its statement suggested that untreated gas, with the carbon left in, would be less welcome than pure hydrogen. Eurogas said that gas “offers quick wins for the energy transition. Switching from coal to gas in power generation would enable the EU to reduce its emissions by an additional 5% by 2030. This is an already available solution to meet the EC's increased greenhouse gas emissions target of 50%." It also said that it was good the EC recognised the importance of developing carbon capture and storage (CCS). “Establishing a policy framework to deliver CCS must be created to produce low carbon gases, namely hydrogen. Having a target for such gases would help the EU to achieve a higher share of renewable energy at lower cost.” It concluded in its September 11 statement that “diversified sources of gas and infrastructure are healthy for the overall performance of the gas market. LNG supplies from the US, Middle East, Egypt and Russia can help the EU increase security of supply at affordable prices. This will help increase industrial competitiveness in the EU.” |

|

Europe’s emissions a tiny percentage: IEA Europe's determined approach to cut CO2 emissions is an "inspiration" to other regions, but ultimately it cannot make much of an impression globally unless other regions follow its example, the boss of the International Energy Agency Fatih Birol told NGW on the sidelines of the World Energy Congress in Abu Dhabi September 10. He said there is a "growing understanding that there is a grave challenge, but I am concerned that there is not enough action to translate this new understanding into reality." Europe is different from Africa and India and other countries, he said, that lack political determination. Europe is the "leader in the fight against climate change but it is responsible for only 9% of global emissions," he said. This is important because mitigation measures, such as the substitution of methane with hydrogen and of fossil gas with synthetic gas, and so on, is expensive and it can also be offset by larger economies emitting more, thanks to heavy reliance on coal, or by natural or manmade disasters and seasonal problems such as forest fires or deliberate deforestation. On the other hand, there is a certain amount of over-simplification of the issues: the older gas-fired plant can be dirtier than the newest, super-critical coal-fired plant. But he said that one should not mix the youth voices in Europe calling for drastic measures with the concerns of India and Bangladesh, where a middle class is arising which has "many other preoccupations," such as eliminating poverty. |