A False Dichotomy

The debate about what happened in Texas in February had a lot of finger pointing. The polar vortex of extreme cold weather, with temperatures in Dallas dropping to -9C on February 15th, set in motion a ‘perfect storm’ of separate, but interconnected energy sector events that brought most of the state’s power down. As a result, 4 million people lost electricity for days, the main source of heating in the state, in the midst of record frigid weather.

This debate featured a lot of blame shifting, and at one point most of the fingers were pointing at either natural gas, or wind generation – creating a false illusion of antagonism between the two energy sources. This was misguided because in reality, gas and wind have been working seamlessly together, until something went wrong system-wide.

This debate featured a lot of blame shifting, and at one point most of the fingers were pointing at either natural gas, or wind generation – creating a false illusion of antagonism between the two energy sources. This was misguided because in reality, gas and wind have been working seamlessly together, until something went wrong system-wide.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

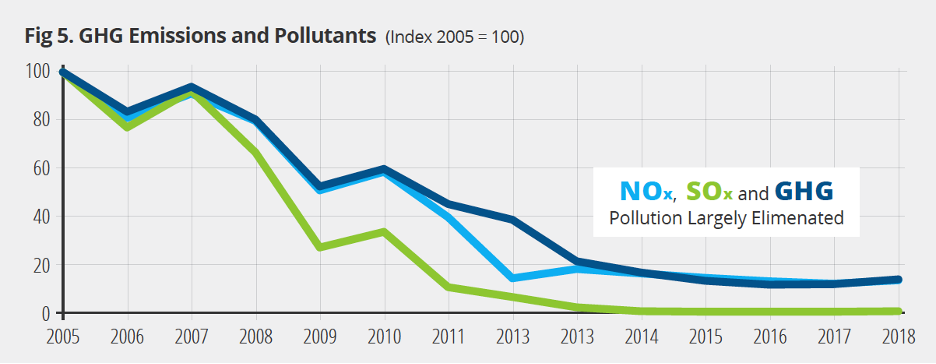

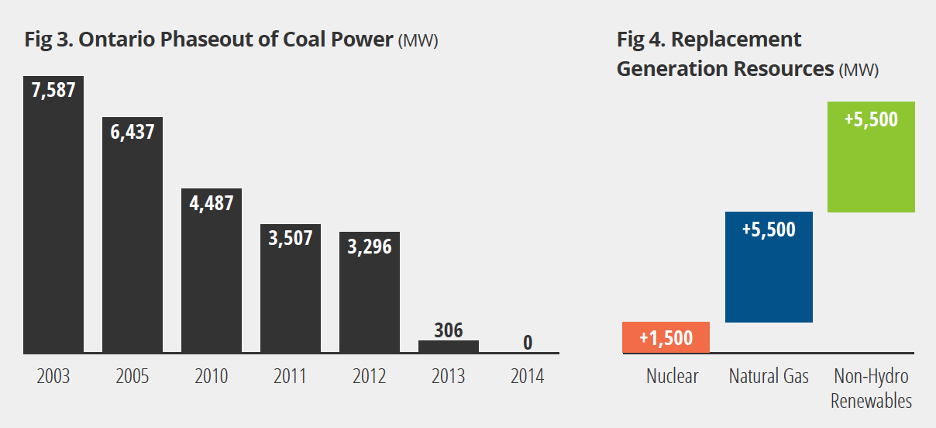

The IGU’s recent report on the role that gas played in the Canadian province of Ontario clean energy transition and in its power system reliability shows this tandem well, and the graph below is case in point. An extreme winter weather period in November of 2019 had gas and wind both supplying a significant share of the electricity load, with gas efficiently balancing the natural variability in wind output. Ontario completed an ambitious transformation of its power system, eliminating all coal power generation from its electricity supply in under a decade. It is now one of North America’s environmental leaders, and its electricity generation is 90% emission-free.

The recent Texas debate creates several false dichotomies: gas vs. renewables, reliability vs. deregulation; radical change vs. total stagnation; caring about the climate vs. supporting the energy sector. Such all or nothing perception is not helpful in understanding the real cause of the problem, nor useful for finding a solution to prevent it from happening again.

Energy systems are complex, multilevel networks of many interdependent pieces of infrastructure, sources of supply, and centres of demand – all of which are often in themselves complex systems, behaving in different ways. Analysing what went wrong requires a systemic view.

In Texas, it was indeed the perfect storm of coinciding factors, as issues piled on from all sides, and all at once – electricity demand surged by almost 10 percent (5.6GW) above the planned winter peak, driving up market price to $9,000 /MWh; supply of gas could not meet additional demand, because production was impacted by the frozen equipment, and more than half of gas generation became unavailable; supply of wind was reduced by half as well; coal plants operated at half capacity; and one of four nuclear facilities shut down.

A deeper analysis of the Ontario case study is available in the IGU’s recent publication, Transitions toward Clean and Reliable Power Systems, which can be downloaded here, and below are the key lessons that it offers to jurisdictions around the world, as they embark on the most ambitious industrial and societal transition of our time – the energy transition.

Key Reliability Lessons from Ontario’s Transition

Diversification:

Diversity of tools and resources, including sufficient dispatchable capacity, provides flexibility and helps to ensure power system reliability.

Demand:

Demand is a resource. Demand side and conservation measures can be highly effective in reducing energy use and provide a valuable reliability resource.

Planning:

Deliberate and robust policy is important for effective transitions, but it should be informed by interdependent expert system planning and supported by an effective regulatory framework.

Pricing:

It is critical to ensure that price signals correctly communicate system needs and priorities, and that the overall market design is aligned with the system reliability requirements.

Pain Points:

Infrastructure bottle necks should be addressed, particularly where multiple networks become interdependent. The Ontario case demonstrated this for the electricity and gas networks, as it ensured sufficient natural gas pipeline and storage infrastructure through a capacity allocation mechanism.

Tatiana Khanberg, IGU